1Independent Researcher, New Delhi, India

2School of Management Studies, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology Allahabad, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Indian expatriates form a significant portion of western countries’ total immigrant population. This study aims to empirically examine the significance of cultural intelligence (CQ) and perceived organisational support (POS) in facilitating Indian expatriates’ cultural adjustment and job satisfaction. We use data from 220 Indian expatriates working in 30 different foreign subsidiaries to examine the proposed hypotheses. First, we validated the collected data using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We then tested the hypothesised relationships through structural equation modelling (SEM). Results indicate that CQ and POS were positively and significantly associated with Indian expatriates’ cultural adjustment and job satisfaction. We also found support for indirect effects where adjustment partially mediated the relationship between the predictors—CQ and POS and the criterion, that is, job satisfaction. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of study findings and also suggest directions for future research.

Perceived organisational support, cultural intelligence, expatriate adjustment, job satisfaction, Indian expatriates

Introduction

The globalisation era has led to companies extending their boundaries beyond their country of origin and establishing operations overseas. With internationalisation, there comes a plethora of challenges that multinational corporations (MNCs) need to handle. These challenges range from the transfer of human resource management policies and practices (Oppong, 2018) to managing the integration and control over subsidiaries’ activities and performance, especially in culturally distant nations (Colakoglu & Caligiuri, 2008). This is where the role of expatriates comes into the picture. Research shows that expatriates play a pivotal role in transferring firm-specific knowledge to subsidiaries, facilitating entry into new local markets, and keeping intact the organisational structure, culture and philosophy of MNCs (Colakoglu & Caligiuri, 2008; Kim & Slocum, 2008; Riusala & Suutari, 2004; Tripathi & Singh, 2021). Therefore, expatriates are not only the mediums to effectuate the success and growth of MNCs but also act as a guiding light for subsidiaries to realise global business objectives (Bhatti et al., 2013; Lee & Sukoco, 2010). However, in the process of ensuring better integration with subsidiaries, expatriates themselves are exposed to a variety of challenges such as adjustment issues, language barriers, lack of cultural awareness and support from the organisation. Consequently, many assignments result in failure and early repatriation causing considerable loss to organisations and expatriates (Kraimer et al., 2009; Singh & Tripathi, 2018; Tripathi & Singh, 2022). Templer (2010) argued that failed assignments may hamper an organisation in several ways. Apart from substantial financial loss, premature returns badly affect organisation productivity, sales and revenues, market size, business opportunities and reputation in the market. Furthermore, assignment failures may also have consequential impacts on employees’ overall well-being and confidence (Kawai & Strange, 2014; Templer, 2010).

Difficulties arising out of living and working in a culturally distinct nation have been extensively discussed in the literature (Kawai & Strange, 2014; Selmer, 2006; Tripathi & Singh, 2022). Management scholars and practitioners have repeatedly touted the importance of cultural adjustment of expatriates and how critical it is for foreign assignments’ success. In addition to this, the last two decades witnessed an increase in the studies on cultural adjustment and its impact on task and contextual performance (Bhatti et al., 2013; Jyoti & Kour, 2017; Kawai & Strange, 2014; Lee & Sukoco, 2010; Mezias & Scandura, 2005; Nunes et al., 2017; Ramalu et al., 2012). However, the topic of expatriate job satisfaction, which is established as a significant determinant of the performance and retention of employees, has often been overlooked by scholars (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., 2005; Froese & Peltokorpi, 2011; Tripathi & Singh, 2020). Employees’ job performance and retention is very important not only from the individual but also from organisation’s success point of view. From individuals’ perspective, job performance leads to satisfaction on job, which is an ultimate driving factor for career satisfaction. Looking from organisations’ point of view, employee retention is more crucial for organisation’s success and realising overall organisational objectives (Cerdin & Le Pargneux, 2014). Hence, employee’s job satisfaction cannot be overlooked especially on foreign assignments. A satisfied employee is more likely to be motivated enough to perform well and remain on the assignment. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to study the factors that influence the job satisfaction of employees on foreign assignments.

In addition, with the increasing global competition and the dependency of MNCs on expatriates for successful business functions and growth (Bhatti et al., 2013), it is imperative to understand why some expatriates are more adjusted and satisfied than others in their international work assignments. In this regard, cultural intelligence (CQ)—a set of intelligent behaviours from the viewpoint of people in specific cultures, is believed to explain the reasons for individual differences in acclimatising to distinct cultural environments (Huff et al., 2014). Introduced by Earley and Ang (2003), this unique facet of intelligence is defined as an individual’s competence to successfully adapt to new and unfamiliar cultural environments. As evident from the recent review conducted by Ott and Michailova (2018), CQ has been widely researched for its effects on cultural adjustment and performance of expatriates. However, even after two decades of its advancement, the effect of CQ on the job satisfaction of expatriates is yet to be explored.

Another important factor that is found to be related to a variety of employee work-related attitudes and outcomes is perceived organisational support (POS). POS indicates ‘employees’ perception of the degree to which organisations care about their well-being and value their contribution in achieving organisational goals’ (Kraimer & Wayne, 2004; Riggle et al., 2009). The meta-analyses on POS and employee outcomes reveal that POS has a strong positive effect on job satisfaction (Ahmed et al., 2015; Riggle et al., 2009). However, the research results in these studies are limited to domestic employment contexts only. Additionally, the relationship of POS with expatriate-related outcomes is still under-researched (Kawai & Strange, 2014). It is important to note that the role of POS becomes even more important in cross-cultural contexts where the support from both the home and host country organisations is equally important for expatriates’ psychological well-being (De Paul & Bikos, 2015).

Based on these rationales, the objective of the present research is to empirically assess the role of CQ and POS in impacting expatriate adjustment and job satisfaction. Studying adjustment and job satisfaction would also be important in understanding the extent to which CQ and POS help expatriates in getting along well in the new country and having positive attitude towards their job. In the absence of such knowledge, MNCs may have a hard time figuring out why expatriates don’t feel contented and what makes them quit the assignment. This investigation is also expected to help MNCs in avoiding the cost incurred due to failed international assignments. We expect three major contributions to expatriation literature from our study. First, we attempt to investigate the effects of CQ and POS on job satisfaction with cultural adjustment as a mediator. Second, the theories of multiple intelligence and organisational support have been followed to determine how CQ and POS affect expatriates’ job satisfaction. The last contribution pertains to the testing of the research model in the Indian context. India has been a major source of expatriates as a large chunk of its population is skilled and English-speaking (Thite et al., 2009; Tripathi & Singh, 2021; Vijayakumar & Cunningham, 2016).

The following section comprises the theoretical background and how the hypotheses have been developed.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

CQ, Cultural Adjustment and Job Satisfaction

CQ was first introduced in an article by Earley (2002) and then in a book titled Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions across Cultures by Earley and Ang (2003). CQ refers to a set of capabilities that allow individuals to function effectively in not just one but a variety of cultural environments. It reflects how well a person utilises cultural cues to adapt to unfamiliar and diverse cultural situations (Ang et al., 2007; Earley & Ang, 2003). CQ is grounded in the theory of multiple intelligences by Sternberg and Detterman (1986) that contend that the concept of intelligence is multidimensional. Thus, despite focusing specifically on culture-related intelligence, CQ is multi-factor in nature (Malek & Budhwar, 2013). The different dimensions of CQ are as follows: meta-cognitive, cognitive, motivational and behavioural (Ang et al., 2007; Earley & Ang, 2003).

The meta-cognitive dimension of CQ refers to the mental processes involved in gaining and interpreting knowledge about different cultures. It makes individuals conscious of when and how to apply their cultural knowledge in cross-cultural interactions Thus, meta-cognition is a high-order mental process that enables a person to plan and control [DEL3] on how to successfully deal with distinct cultural scenarios (Ang et al., 2007). The cognitive CQ refers to a person’s knowledge structures and understanding of similarities and differences across cultures. It reflects how well a person is aware of other cultures’ values, norms and practices (Ang et al., 2007; Triandis, 1994). The motivational dimension of CQ displays one’s readiness to learn and understand cultural diversity and the desire to interact with people from different cultures (Earley & Peterson, 2004). Finally, the behavioural dimension of CQ refers to the capability to exhibit appropriate actions and behaviours in different cultural interactions. It includes the manifestation of suitable verbal and normal verbal behaviours while interacting with people from different cultures (Ang et al., 2007).

People with high CQ are expected to make better cultural judgements and easily assimilate into new cultures since they have the repertoire to predict the desired actions and behaviours expected in a given culture. They are mindful and conscious of the norms, practices and preferences of a culture and can make better decisions about how to respond effectively during intercultural interactions (Ang et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2017).

Therefore, using the above arguments, we can conclude that high CQ makes a person better attuned to the nuances of distinct cultural settings and facilitates an easy adaptation to different cultures. Previous studies on CQ have established it as a significant predictor of cultural adjustment (Lee & Sukoco, 2010; Lee et al., 2014). Researchers have also found a positive relationship between CQ and job performance (Lee & Sukoco, 2010; Ramalu et al., 2012). Using these supportive shreds of evidence, we suggest that CQ is likely to have a positive influence on job satisfaction as well. CQ’s positive impact on job performance signifies that cultural knowledge and awareness assist expatriates in better understanding and conforming to the role expectations in a new culture. Likewise, a better understanding of role expectations may also lead to an increase in job satisfaction of expatriates, since they have the confidence that they can effectively respond to challenges caused by cultural differences at the workplace. Accordingly, we hypothesise that the following:

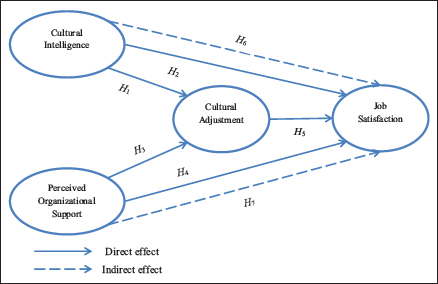

H1: CQ has a significant and positive effect on expatriate cultural adjustment.

H2: CQ has a significant and positive effect on expatriate job satisfaction.

POS, Cultural Adjustment and Job Satisfaction

The concept of POS has been deeply rooted in organisational support theory, which proposes that employees infer the sense of support and care from the organisation through various policies, procedures and treatments. If the employees believe that these policies and practices are committed to promoting their best interests, then they reciprocate this support with the socio-emotional resources that they have in the form of trust, commitment, loyalty, dedication and performance (Kawai & Strange, 2014; Kraimer & Wayne, 2004; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

The relationship between organisational support and employees’ commitment is also contained in social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), which is grounded in the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960). The concept of social exchange and reciprocity is based on the assumption that the employees feel obliged to the favourable support they receive from the organisations, and thus, reciprocate this support with increased commitment, performance and loyalty (Kawai & Strange, 2014). Thus, POS can be summed up as ‘employees’ global beliefs that the organisation values their contributions and cares about their well-being’ (Kraimer & Wayne, 2004; Riggle et al., 2009).

POS has the following three main dimensions: career POS, finance POS and adjustment POS (Kawai & Strange, 2014; Kraimer & Wayne, 2004; Kraimer

et al., 2001). Career POS refers to the level of care and support demonstrated by organisations to develop expatriates’ careers during their stay on assignment and also after their repatriation. Finance POS is described as the extent to which organisations support expatriate employees with their financial needs, such as bonuses, allowances and insurance. Finally, adjustment POS means the pre-departure training and relocation assistance provided by organisations to expatriates and their families to facilitate an easy transition after their transfer to the foreign nation. All these kinds of support help employees deal effectively with cultural challenges, make them more committed to their organisations and also enhance their performance (Kawai & Strange, 2014; Kraimer & Wayne, 2004; Wu & Ang, 2011).

The application of POS in cross-cultural employment contexts has given a new dimension to our understanding of how organisations can help expatriates deal with adjustment and job-related challenges (De Paul & Bikos, 2015).

The significance of POS in enhancing employee outcomes is well-established in the literature. Researchers and practitioners have argued that how expatriates perceive support from organisation can largely impact their overall well-being, such as happiness, psychological satisfaction and self-realisation (De Paul & Bikos, 2015; Kraimer et al., 2001). Bader (2015) has also reported a positive influence of POS on the work attitude and well-being of expatriate employees. Empirical studies, which investigated POS in international context, found it to be a crucial determinant of adjustment, commitment towards organisation and employee turnover intentions (Kraimer et al., 2001). It has also been argued by researchers that employees who experience supporting organisational climate show greater citizenship behaviour and commitment towards their organisation (Liu & Ipe, 2010). Prior studies have also found a positive relationship between POS and expatriate adjustment. Likewise, favourable and good organisational support is believed to positively influence the job satisfaction of employees. The perceived care and support from the organisation may stimulate in expatriates a sense of being valued by the organisation making them more satisfied with their jobs. Therefore, people with good POS may feel better adjusted to cultural dissimilarities and are expected to be greatly satisfied in their work front. On the basis of these arguments, the following is proposed:

H3: POS has a significant and positive effect on expatriate cultural adjustment.

H4: POS has a significant and positive effect on expatriate job satisfaction.

Cultural Adjustment and Job Satisfaction

Cultural adjustment is well-established in the literature as a critical predictor of successful expatriate assignments (Palthe, 2004). It has been defined as ‘expatriates’ degree of psychological comfort and familiarity with the new culture’. Simply put, cultural adjustment reflects how comfortably expatriates imbibe the tenets of the host country while living and working there (Black, 1988; Black et al., 1991; Black & Stephens, 1989). It is conceptualised as a construct comprising the following three dimensions: general, work and interaction adjustment (Black et al., 1991).

The general adjustment refers to the extent to which expatriates are comfortable with the various aspects of general living conditions in the host country, such as food, weather and transportation system. Work adjustment signifies psychological comfort with the demands of the new work environment, such as job tasks, responsibilities, leadership and role expectations. Interaction adjustment is the degree of comfort while interacting with locals in the host country (Black & Stephens, 1989).

Prior literature shows that cultural adjustment has a significant effect on expatriate outcomes, such as performance, turnover intentions, organisational citizenship behaviour and organisational commitment—all of which have been established as the consequence of job satisfaction (Barakat et al., 2015). Hence, cultural adjustment is expected to positively affect job satisfaction as well.

H5: Cultural adjustment has a significant and positive effect on expatriate job satisfaction.

The Mediating Role of Cultural Adjustment

Over the years, cultural adjustment has been established as a fundamental and primary outcome that is responsible for shaping other consequences of cross-cultural assignments, such as performance, effectiveness and commitment (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., 2005; Kim & Slocum, 2008).

According to Kraimer et al. (2001) and Kawai and Strange (2014), positive and favourable organisational support help expatriates better adapt to cross-cultural environments. Not only this but POS has also been established as a strong contributor to the psychological well-being of expatriates (De Paul & Bikos, 2015). Psychological comfort and adjustment in the host country increase the job satisfaction of expatriates (Takeuchi et al., 2002). Thus, it can be argued that POS is an incredible assistance from organisation, helping expatriates adapt to the new culture and experience greater job satisfaction.

Similarly, the role of CQ has proved to be pivotal in determining the adjustment of expatriates (Guðmundsdóttir, 2015; Lee & Sukoco, 2010). Moreover, studies have also proposed that cultural adjustment mediates the positive impact of CQ on expatriate performance (Ramalu et al., 2012). In addition, performance being a criterion of job satisfaction gives us a base to propose that cultural adjustment will mediate the positive effect of CQ on job satisfaction as well.

We propose cultural adjustment as a mediating variable in this study. The role of a mediator is to expound on the causal relationship between the antecedent and consequence (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Accordingly, we propose that adjustment as a mediating variable will facilitate the positive association between the antecedents (i.e., CQ and POS) and the consequence (i.e., job satisfaction). The hypotheses that are formulated are as follows:

H6: Cultural adjustment mediates the relationship between CQ and job satisfaction.

H7: Cultural adjustment mediates the relationship between POS and job satisfaction.

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesised path relationships.

Figure 1. Hypothesised Model.

Methodology

Data Collection

To test the proposed model, we gathered data from the Indian-origin expatriates currently working in foreign countries. A questionnaire prepared in English was used to solicit the responses. The study participants were acquired through convenience and snowball sampling. Our respondents were selected from multiple sources. First, an online survey link was mailed to expatriate managers from management program alumni lists and researchers’ own references, requesting them to participate in the study. We also requested these managers to send the survey to expatriates from their contact list. To collect more responses, we approached the Indian expatriates’ groups and communities on the internet. In total, 234 responses were collected; however, 8 were discarded for being outliers and 6 were deleted because of unengaged responses. Finally, 220 usable questionnaires were included in the analysis.

Measurement

To measure CQ, we used items from the cultural intelligence scale (CQS) developed by Ang et al. (2007). We asked the expatriates to rate their disagreement or agreement with statements on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’. The sample item is ‘I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds’.

We measured the POS with Kraimer and Wayne’s (2004) scale. We asked the expatriates about their perceived degree of support from the organisation on a five-point scale, where 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 = ‘strongly agree’. One sample question is ‘The financial incentives and allowances provided to me by my organisation are good’.

To measure the degree of cultural adjustment, we adopted items from Black’s (1988) scale. Sample item includes ‘How adjusted are you to the weather in foreign?’ A five-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘not adjusted at all’ to 5 = ‘very well adjusted’ was used.

We measured the job satisfaction of expatriates with West et al.’s (1987) scale. We asked the respondents to rate how satisfied they were with their job on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’. The sample question is ‘I’m satisfied with my performance in the job’.

Common Method Variance

Since all our study variables were rated by a single source, that is, expatriates, there is a potential for method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To address this issue, we assured the respondents that their responses would be confidential and anonymous. Further, while designing the questionnaire, we randomly placed the items for the predictor and criterion variables. We also ensured that all questions in the questionnaire can be easily comprehended. Finally, we used Herman’s single-factor test by loading each construct item on a single factor (Harman, 1976; Podsakoff et al., 2003). The un-rotated principal component analysis (PCA) resulted in the first factor explaining 42.92% of the variance, which is below 50% and does not constitute a majority of the variance (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Hence, it can be assumed that common method variance (CMV) is not concerning in the used data set.

Analysis and Results

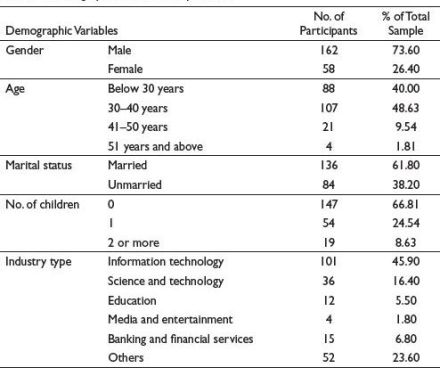

We used SPSS and AMOS 22.0 to conduct the data analyses. First of all, we discussed the sample characteristics by presenting the demographic profile of respondents. The sample consisted of 220 Indian nationals expatriated to 30 foreign countries. In regards to the gender distribution, most of them were male (73.6%) and in the age bracket of 30–40 years (48.6%). 61.8% of the respondents were married and 33.1% were with kids. The participants came from multiple sectors, that is, IT, science and technology, education, media and entertainment, banking and financial services, and others. Table 1 presents the demographic profile of respondents.

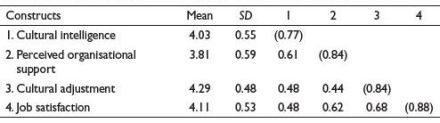

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of variables, that is, means, standard deviations, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and correlations between constructs. Alpha values ranging from 0.77 to 0.88 indicate good internal consistency reliability of study variables (Nunnally, 1978).

Table 1. Demographic Profile of Respondents.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Constructs.

Notes: N = 220.

Correlations are significant at p < .01 (two-tailed).

Values within parentheses represent reliabilities.

We followed the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and checked the distinctiveness of constructs first. To do that, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the convergent and discriminant validity. In the next step, we used structural equation modelling (SEM) to test our hypothesised path relationships.

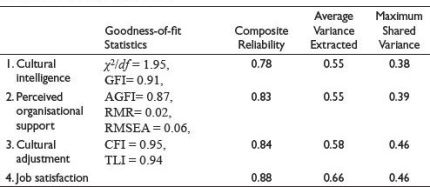

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We first performed CFA to test the measurement model. Items with standardised regression weight (SRW) less than 0.50 were deleted (Hair et al., 2010). The overall model fit was assessed based on the chi-square (χ2) value and other global fit indices such as Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Root Mean Squared Error (RMR), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). Table 3 presents the results for the overall measurement model. The statistics for global fit indices indicate that the values satisfy the relevant thresholds and the data adequately fit the model (Byrne, 2001; Chau, 1997). Furthermore, the average variance explained (AVE) greater than 0.50 and the composite reliability (CR) greater than 0.70 for all constructs establishes the convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). In addition, the AVE values exceeding the maximum shared variance (MSV) ensure the discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2010).

Structural Equation Modelling

We used the SEM to test the hypothesised path relationships. This study examines the relationship between CQ, POS, cultural adjustment and job satisfaction using the imputation method in AMOS. We followed the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes (2004) to test the mediating effects of cultural adjustment.

To test the direct relationships, we first analysed the impact of CQ on cultural adjustment and job satisfaction. The results indicated that CQ has a significant effect on both adjustment (β = 0.56, p < .001) and job satisfaction (β = 0.55, p < .001) of expatriates. Hence, hypotheses H1 and H2 stand accepted. Similar results were found for the effect of POS on adjustment (β = 0.52, p < .001) and job satisfaction (β = 0.70, p < .001), indicating support for hypotheses H3 and H4.

Finally, the calculation for the effect of the cultural adjustment on job satisfaction was also found to be significant (β = 0.76, p < .001). Thus, H5 was supported.

Table 3. The Measurement Model.

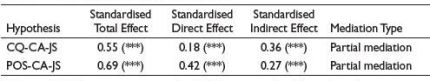

Table 4. Bootstrapping Results for Mediation.

Notes: n = 2,000 bootstrapping resamples, 95% bias-corrected confidence interval.

***p < .001.

CQ = Cultural intelligence; POS = Perceived organisational support; CA = Cultural adjustment;

JS = Job satisfaction.

In order to determine the indirect effects, the mediating variable, that is, cultural adjustment was put between the independent and dependent variables. A bootstrap method was used to estimate the indirect effect. Table 4 presents the bootstrapping results which show a significant indirect effect of both CQ (β = 0.36, p < .001) and POS (β = 0.27, p < .001) on job satisfaction through cultural adjustment. Accordingly, hypotheses H6 and H7 were supported.

Furthermore, cultural adjustment partially mediates the relationship between the predictors, that is, CQ and POS, and the outcome variable job satisfaction, as the direct effects of both CQ (β = 0.18, p < .001) and POS (β = 0.37, p < .001) on job satisfaction remained significant in the presence of the mediator. Hence, support for all seven hypotheses was obtained in the present study.

Discussion

This study investigates how CQ and POS influence the job satisfaction of Indian expatriates directly and indirectly. Drawing on multiple intelligences theory and the theory of organisational support, we developed a model investigating relationships among CQ, POS, cultural adjustment and job satisfaction of Indian international assignees. We sought to explore the following two issues: first, the direct impact of CQ and POS on job satisfaction; and second, the indirect impact of cultural adjustment between the predictors, that is, CQ and POS, and the outcome variable job satisfaction. The results of statistical analyses revealed that both CQ and POS were positively and significantly associated with cultural adjustment and job satisfaction of Indian expatriates. CQ was found to explain 32% and 31% of the variance in cultural adjustment and job satisfaction, respectively. Similarly, POS accounted for 27% of the variance in cultural adjustment and 49% of the variance in job satisfaction. This finding helps us in concluding that Indian expatriates who have high CQ and who believe that their organisation cares about their well-being tend to demonstrate greater adjustment and are more likely to be satisfied with their job.

Moreover, the present study gathered support for the effect of the cultural adjustment on job satisfaction of Indian expatriates. Therefore, it can be concluded that expatriates who are able to adjust and get along well in distinct cultural contexts are also satisfied with their job and work aspects.

We argue that expatriates with high CQ are better able to handle the intricacies of a new culture by utilising their cultural cues to develop an effective understanding of different cultures and exhibiting the desired responses in various cross-cultural interactions. This simplifies the overall adjustment process and also leads to more satisfaction with the job. Our findings are in line with Guðmundsdóttir (2015) and Lee et al. (2014) in demonstrating the usefulness of CQ in cross-cultural scenarios.

We also argue that expatriates’ adjustment in foreign nations becomes easy if positive and favourable support is obtained from the organisation. Perception of favourable organisational support may help expatriates believe that their organisation would be there to support them in situations of need. This feeling may help them get along well with new culture and workplace environment. Our findings are consistent with the results of Caligiuri et al. (1999), and Kraimer

et al. (2001) who suggested that organisational support is significantly associated with cross-cultural adjustment and job satisfaction.

The present study also calculated the effect of CQ and POS on job satisfaction when the mediator, that is, cultural adjustment was inserted. The results showed support for partial mediation of cultural adjustment on the relationship between the predictors (CQ and POS) and job satisfaction. This means that the total variance in job satisfaction accounted for by CQ and POS is partly caused by their direct influence, and partly caused by their indirect influence mediated through cultural adjustment. Simply put, an increase in CQ and POS of expatriates leads to an increase in their adjustment to the host country, which in turn leads to an increase in their job satisfaction.

Theoretical and Managerial Implications

Our research supplements the expatriation literature in four ways. First, both our predictor variables, that is, CQ and POS were drawn from relevant theories, thus providing a strong foundation to the proposed conceptual model. Second, although several studies have investigated the consequences of CQ; a few have investigated beyond adjustment and performance (Ott & Michailova, 2018). Our study examined the impact of CQ on a critical organisational outcome, that is, job satisfaction, and found positive support for its role in influencing expatriates’ job satisfaction. Third, our study is among the few that investigated the cross-cultural consequences of Indian expatriates; a population that constitutes a significant portion of western countries’ total immigrant population (Shah & Barker, 2017; Vijayakumar & Cunningham, 2016). Finally, our study is an addition to the limited research on expatriates from developing countries. The literature on cross-cultural assignments is dominated by MNCs from western countries (Zhao et al., 2016). Therefore, our study contributes to the extension of expatriation literature to developing countries.

The results of the study helped in suggesting some managerial implications as well that may help organisations preventing assignment failure. The positive relationships between POS, cultural adjustment and job satisfaction suggest that organisations may devise plans on building up good and conducive relationships with expatriating employees in order to help them adapt well to distinct cultural settings and contribute towards the success of the assignment. Organisational support should be extended by both the parent country organisation as well as the subsidiary. Furthermore, organisations may also devise plans for assisting the families of expatriating employees and help them deal with logistical issues that may arise. The support for the family by organisation may help expatriates be at ease and focus more on their work duties. Improved organisational support could increase the efficiency of expatriates and result in the overall success of the assignment.

Similarly, considering the crucial role played by CQ in cross-cultural assignments, organisations should incorporate it in their selection and training criteria before sending their employees on foreign assignments. Additionally, interesting and unique facts about the host country’s culture should be shared in advance with the expatriating employees to help them develop cultural awareness. In addition, organisations should strive to provide employees with all relevant information relating to the new assignment to facilitate an easy transition. Contact information of existing expatriates in the given host country can also be shared with new expatriating employees to provide them with the social support that they might need during the initial days of the assignment.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Like every research, this study has a few shortcomings that may impact its contributions and generalisability. However, these shortcomings open several avenues for further research. First of all, the study sample comprised Indian expatriates only, which limits the generalisability of the results. India is a highly diversified country that encompasses a variety of cultures; therefore, Indians may be comfortable understanding the nuances of different cultural settings. It would be interesting to see if the study findings hold true for expatriates of other nations and origins. Next, the study contained only one dependent variable, that is, job satisfaction. Future researchers may explore other criterion variables such as organisational commitment, engagement and knowledge transfers. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study. In the future, longitudinal studies can be conducted to check how the relationship between CQ, POS, adjustment and satisfaction varies over time. Lastly, the self-reported questionnaires used in the study may pose the risk of CMV. Although we employed certain methodological remedies to alleviate its effects, the presence of

method bias cannot be completely ruled out. To address this issue, future research works could use a combination of self-report and peer/spouse-report surveys to enhance the power and reliability of results.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ahmed, I., Nawaz, M. M., Ali, G., & Islam, T. (2015). Perceived organizational support and its outcomes: A meta-analysis of latest available literature. Management Research Review, 38(6), 627–639.

Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Some methods for re-specifying measurement models to obtain uni-dimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 453–460.

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N. A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision-making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371.

Bader, B. (2015). The power of support in high-risk countries: Compensation and social support as antecedents of expatriate work attitudes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(13), 1712–1736.

Barakat, L. L., Lorenz, M. P., Ramsey, J. R., & Cretoiu, S. L. (2015). Global managers: An analysis of the impact of cultural intelligence on job satisfaction and performance. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 10(4), 781–800.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 257–281.

Bhatti, M. A., Battour, M. M., & Ismail, A. R. (2013). Expatriates adjustment and job performance: An examination of individual and organizational factors. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(7), 694–717.

Black, J. S. (1988). Work role transitions: A study of American expatriate managers in Japan. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(2), 277–294.

Black, J. S., Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (1991). Toward a comprehensive model of international adjustment: An integration of multiple theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 291–317.

Black, J. S., & Stephens, G. K. (1989). The influence of the spouse on American expatriate adjustment and intent to stay in Pacific Rim overseas assignments. Journal of Management, 15(4), 529–544.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. Wiley.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Caligiuri, P. M., Joshi, A., & Lazarova, M. (1999). Factors influencing the adjustment of women on global assignments. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10(2), 163–179.

Cerdin, J. L., & Le Pargneux, M. (2014). The impact of expatriates’ career characteristics on career and job satisfaction, and intention to leave: An objective and subjective fit approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(14), 2033–2049.

Chau, P. Y. K. (1997). Reexamining a model for evaluating information center success using a structural equation modeling approach. Decision Sciences, 28(2), 309–334.

Colakoglu, S., & Caligiuri, P. (2008). Cultural distance, expatriate staffing and subsidiary performance: The case of US subsidiaries of multinational corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(2), 223–239.

De Paul, N. F., & Bikos, L. H. (2015). Perceived organizational support: A meaningful contributor to expatriate development professionals’ psychological well-being. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.004

Earley, P. C. (2002). Redefining interactions across cultures and organizations: Moving forward with cultural intelligence. Research in Organizational Behavior, 24, 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(02)24008-3

Earley, P. C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford University Press.

Earley, P. C., & Peterson, R. S. (2004). The elusive cultural chameleon: Cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(1), 100–115.

Froese, F. J., & Peltokorpi, V. (2011). Cultural distance and expatriate job satisfaction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(1), 49–60.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178.

Guðmundsdóttir, S. (2015). Nordic expatriates in the US: The relationship between cultural intelligence and adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.05.001

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspectives (7th ed.). Pearson.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Huff, K. C., Song, P., & Gresch, E. B. (2014). Cultural intelligence, personality, and cross-cultural adjustment: A study of expatriates in Japan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.005

Jyoti, J., & Kour, S. (2017). Cultural intelligence and job performance: An empirical investigation of moderating and mediating variables. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 17(3), 305–326.

Kawai, N., & Strange, R. (2014). Perceived organizational support and expatriate performance: Understanding a mediated model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(17), 2438–2462.

Kim, K., & Slocum, J. W. (2008). Individual differences and expatriate assignment effectiveness: The case of US-based Korean expatriates. Journal of World Business, 43(1), 109–126.

Kraimer, M. L., Shaffer, M. A., & Bolino, M. C. (2009). The influence of expatriate and repatriate experiences on career advancement and repatriate retention. Human Resource Management, 48(1), 27–47.

Kraimer, M. L., & Wayne, S. J. (2004). An examination of perceived organizational support as a multidimensional construct in the context of an expatriate assignment. Journal of Management, 30(2), 209–237.

Kraimer, M. L., Wayne, S. J., & Jaworski, R. A. A. (2001). Sources of support and expatriate performance: The mediating role of expatriate adjustment. Personnel Psychology, 54(1), 71–99.

Lee, L. Y., & Sukoco, B. M. (2010). The effects of cultural intelligence on expatriate performance: The moderating effects of international experience. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(7), 963–981.

Lee, L. Y., Veasna, S., & Sukoco, B. M. (2014). The antecedents of cultural effectiveness of expatriation: Moderating effects of psychological contracts. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(2), 215–233.

Liu, Y., & Ipe, M. (2010). The impact of organizational and leader–member support on expatriate commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(7), 1035–1048.

Malek, M. A., & Budhwar, P. (2013). Cultural intelligence as a predictor of expatriate adjustment and performance in Malaysia. Journal of World Business, 48(2), 222–231.

Mezias, J., & Scandura, T. (2005). A needs-driven approach to expatriate adjustment and career development: A multiple mentoring perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(5), 519–538.

Nunes, I. M., Felix, B., & Prates, L. A. (2017). Cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation and expatriate performance: A study with expatriates living in Brazil. Revista de Administração, 52(3), 219–232.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

Oppong, N. Y. (2018). Human resource management transfer challenges within multinational firms: From tension to best-fit. Management Research Review, 41(7), 860–877.

Ott, D. L., & Michailova, S. (2018). Cultural intelligence: A review and new research avenues. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 99–119.

Palthe, J. (2004). The relative importance of antecedents to cross-cultural adjustment: Implications for managing a global workforce. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(1), 37–59.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Ramalu, S., Rose, R. C., Kumar, N., & Uli, J. (2012). Cultural intelligence and expatriate performance in global assignment: The mediating role of adjustment. International Journal of Business and Society, 13(1), 19–32.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Riggle, R. J., Edmondson, D. R., & Hansen, J. D. (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 1027–1030.

Riusala, K., & Suutari, V. (2004). International knowledge transfers through expatriates. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46(6), 743–770.

Selmer, J. (2006). Language ability and adjustment: Western expatriates in China. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(3), 347–368.

Shah, D., & Barker, M. (2017). Cracking the cultural code: Indian IT expatriates’ intercultural communication challenges in Australia. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 17(2), 215–236.

Singh, T., & Tripathi, C. M. (2018). Issues related to international work assignments and expatriation: A thematic analysis. FocusWTO/IB, 20(4), 18–33.

Sternberg, R. J., & Detterman, D. K. (1986). What is intelligence? Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Takeuchi, R., Yun, S., & Tesluk, P. E. (2002). An examination of crossover and spillover effects of spousal and expatriate cross-cultural adjustment on expatriate outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 655–666.

Templer, K. J. (2010). Personal attributes of expatriate managers, subordinate ethnocentrism, and expatriate success: A host-country perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(10), 1754–1768.

Thite, M., Srinivasan, V., Harvey, M., & Valk, R. (2009). Expatriates of host-country origin: Coming home to test the waters. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(2), 269–285.

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behaviour. McGraw Hill.

Tripathi, C. M., & Singh, T. (2020). An empirical investigation of the job satisfaction of Indian expatriates: The mediating role of cultural adjustment [Paper presented]. Proceedings of the Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode, India, 21–26. https://forms.iimk.ac.in/research/ds2020/DS2020_Symposium_Proceedings.pdf

Tripathi, C. M., & Singh, T. (2021). An empirical analysis of the willingness for expatriation assignment: The role of career motivation and parental support. SCMS Journal of Indian Management, 18(4), 112–126.

Tripathi, C. M., & Singh, T. (2022). Sailing through the COVID-19 pandemic: Managing expatriates’ psychological-well-being and performance during natural crises. Journal of Global Mobility, 10(2), 192–208.

Vijayakumar, P. B., & Cunningham, C. J. (2016). Cross-cultural adjustment and expatriation motives among Indian expatriates. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 4(3), 326–344.

West, M. A., Nicholson, N., & Rees, A. (1987). Transitions into newly created jobs. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60(2), 97–113.

Wu, P. C., & Ang, S. H. (2011). The impact of expatriate supporting practices and cultural intelligence on cross-cultural adjustment and performance of expatriates in Singapore. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(13), 2683–2702.

Zhao, S., Liu, Y., & Zhou, L. (2016). How does a boundaryless mindset enhance expatriate job performance? The mediating role of proactive resource acquisition tactics and the moderating role of behavioural cultural intelligence. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(10), 1333–1357.