1 Textile Design Department, National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, Delhi, India

2 Knitwear Design Department, National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, Delhi, India

3 Department of Fashion Technology, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Hauz Khas, New Delhi, Delhi, India

4 Textile Design Department, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Kota Doriya is a fabled woven fabric originating from India. It has a unique weave structure and is woven using a technique which makes it different from the rest. This research aims to document the journey of the magical Kota Doria which is disguised in mystery and folktales. The woven Kota Doriya has been awarded the Geographical Indication tag by UNESCO in July 2005. This article elucidates on the techniques adopted by the weavers, which makes the Kota fabric a unique fabric and a testimony to the superior weaving traditions of India. The ‘Ansari’ Muslim community of the Hadauti region largely practices this weaving apart from other regions like the Bundi and Baran districts of Rajasthan. With the large-scale advent of the mechanised loom and synthetic yarns, cheaper imitations of Kota have posed a serious threat to the survival of this craft. Through this research, the timeless Kota fabric will be studied and the current trials and challenges will be assessed. This study is conducted through a combination of secondary, as well as, primary research methods including a case study on the master craftsman of Kota Doriya weaving.

Kota Doriya, yarns, traditional weaving, checks, sustainability, geographical indication (GI)

Introduction

District Kota is located in the south of Rajasthan and on the banks of the Chambal River. This area is occupied with clusters of skilful weaving communities. The whole day long the weavers are occupied in creating one of the finest handloom fabrics known as Kota Doriya. Within Kota, there is a small village called Kaithoon which is recognised for producing the most beautiful Kota Doria fabrics. Geographically, Kota is made of rich black soil in the middle of a desert. The Chambal River converts the dry desert air into a cool moistened breeze which helps in the agriculture of long-fibred cotton plants. This fine cotton is the raw material needed to create the beautiful and delicate Kota Doria. In the olden times, Kota was made of pure cotton yarns. The term ‘Doria’ means ‘thread’ as this exquisite fabric is created by mixing different counts of threads. The distinguishing factor of the Kota Doriya is the exquisite chequered-weave structure which can be traced back to the former kingdom of Mysore. Its main usage was for tying royal turbans for the nobles before it began to be made as opulent sarees mostly in the pastel shades of white and beige. Currently, Kota fabric has faced challenges from machine-made replicas.

Literature Review

Kota Doriya is one of the finely woven open-weave traditional textiles of India (Rana, 2020). An open-weave textile is a fabric which has been woven in such a way that there are inbuilt perforations in its structure (vintagefashionguild, 2012). In other words, the weave creates spaces in-between the warp and the weft yarns (Tariq, 2022). These types of fabrics are used in both home and apparel products because of their qualities of translucency, striking texture, light filtering effects, and water and air permeability (Robertson, 1950). The open-weave structure of Kota Doria is unique because of the distinct square check pattern (Luniya & Agarwal, 2012). It is an airy and lightweight fabric which is suitable to endure the harsh Indian summers. Added to this Kota Doriya requires less maintenance making it a choice for Indians, especially women. The weave originated from Mysore and therefore the fabric was also called Kota Masuria (Hada & Kumar, 2014. Kota fabric was traditionally used as Pagri (headgear) and Sari . Currently, silk is added to cotton to bring down the cost and maintenance of the fabrics (Rana, 2020). Adding silk also adds to the strength and lustre of the fabric. Kota is traditionally created using real gold and silver threads (zari) in diverse geometric and floral patterns. Design interventions in the form of weave and colour effect, double-cloth, coloured extra warp and weft insertions (meenakari) and ikat techniques are used to create new looks in the Kota Doria fabric .

Kota is also found to have a major participation of skilled women weavers (Hada & Kumar, 2014; Sanadhya & Rehman, 2016).

Research Objectives

This research aims for the following objectives:

1. To understand the legacy of Kota Doriya.

2. To provide an overview of the challenges faced by Kota Doriya in the present times.

Hypothesis

This research progresses on the following hypothesis:

Research Methodology

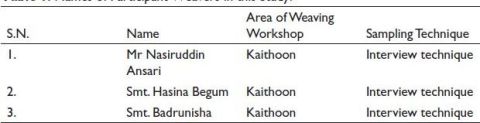

This research follows the mixed research technique of primary and secondary research methods. Table 1 shows the number of participant weavers in this study, their area of work and the sampling technique used for data collection. The following flow chart depicts the research methods followed in this study (refer to Figure 1)

Table 1. Names of Participant Weavers in this Study.

Figure 1. A Flow Chart Depicting the Research Methods Followed for this Study.

Research Findings and Discussion

The researcher met the National Award-winning Kota weaver Mr Nasiruddin Ansari who spoke about the folktale of Kota. According to him, Kota Doriya is a traditional woven fabric from Rajasthan. Mr Ansari recounted the tale of Kota which started in the 16th century AD. The king of Kota, Raja Rao Kishor Singhji visited the King of Mysore. In those days, there was a tradition of gifting between the kings of different places.

The Mysore king gifted weavers to Raja Kishor Singhji who settled them in a small village Kaithoon near the Chandloi River which was 15 km away from Kota. The weavers set up looms there and started making thick fabrics initially. Rao Kishor Singhji gave the weavers all facilities like land, water etc. The weavers later got inspired from Dhakai Muslin and started weaving fine fabric which they gifted to Raja Kishor Singhji. Soon fine fabrics began to be worn by the general public. More people joined the weavers and learned the art of weaving. This generated employment among the people. There was a haat (bazaar) in Kaithoon town which sold fine fabrics and people came from all regions to buy fabrics from there. Apart from Kaithoon where Kota Doria fabrics are mostly woven other Kota Doria weaving clusters can also be found in the smaller towns of Bundi and Baran although Kaithoon remains the main centre of Kota production.

In the 19th century, Rao Kishor Singji's grandson Maharao Bhim Singhji received a gift of silk yarns from the King of Mysore. The Kota fabrics are distinguished by small square textures made throughout the fabric. Each square is known as ‘Khat’ which is made up of a series consisting of four cotton, two silk, two cotton, two silk, two cotton, two silk (i.e., a total of 14 warp threads in one Khat). The total width of the sari is 48 inches with a sum of 300 Khats in the whole width of the fabric (excluding the borders). The cotton threads are 120 CC and the silk is procured from China. Twelve threads of silk and 16 threads of cotton yarn are placed in the warp repeat. Kota’s signature square grid texture gives it a distinguished look and makes Kota different from other fabrics. Every Kota design goes through a rigorous process of conversion onto graphs before it can be finally woven.

Cowdung, bark of the Arjan tree, local plants, etc. are used to colour the Kota fabrics. Division of labour in the Kota weaving saved time and made the work not only superior but also easier. The Kota fabric was woven from the back side meaning the back side of the fabric faced the weaver while weaving. The designs were checked by the weaver by using a mirror (Figure 2). The Kota weavers were called Masuria in olden times and thus Kota Doriya saris are also called Kota Masuria saris. Traditionally Kota fabrics were used to make safa or turbans for the royalties, but later they began to be used as saris.

The weaving process of Kota has remained the same for 400 years. Zari was introduced and bought from Surat around 90 years back which began to be incorporated in Kota fabrics. Fake Kotas from regions of Banaras and other cities began to surface around 50 years back during the 1970s. Five Kota saris were given labour charges of .png) 40 whereas Banaras weavers were given labour charges of

40 whereas Banaras weavers were given labour charges of .png) 15 for five saris as they were woven faster with power looms and with the usage of synthetic zari.

15 for five saris as they were woven faster with power looms and with the usage of synthetic zari.

Figure 2. The Kota Fabric is Woven Upside Down and the Front Design can be Seen Here with the Help of a Mirror.

Figure 3. Insertion of Extra Real Zari Weft and Colourful Yarns to Form Beautiful Patterns in the Kota Sari Made from the Reverse Side.

Kota weavers believed it is their dharma to use real zari for its distinct look which preserved the delicate beauty of the Kota Fabric (Figure 3 shows the weaving of Kota using real zari). The Kota weavers did not adapt to the cheaper substitutes. The weaving of the original Kota Doria is very time-consuming and demands expertise, proficiency, patience and concentration. As a result, it became very expensive in comparison to a cheaper similar-looking product. People stopped buying Kota saris and weavers reduced their production.

However, the Government of India took many initiatives to revive the Kota handloom. Mr Ashwini Saxena, Chief Executive Officer at JSW Foundation, started the act of reviving Kota and proposed GI recognition for Kota Doriya during Atal Bihari Vajpayee's Government (1999–2004). When the erstwhile chief minister of Rajasthan Ms Vasundhara Raje Sindhia came to power she called the weavers to Jaipur and asked about their difficulties in manufacturing and marketing Kota Doriya. Later, she widely promoted Kota Doria saris nationally and internationally which greatly benefitted the Kota weavers. These efforts helped the Kota handloom fabric to become a brand the world over. The unique structure of Kota Doriya encouraged the Kota Doria Development Hadauti Foundation (KDHF) to file for the GI mark with the help of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) Kota Doriya was granted the GI mark on 5 July 2005 under the Geographical Registration Act 1999.

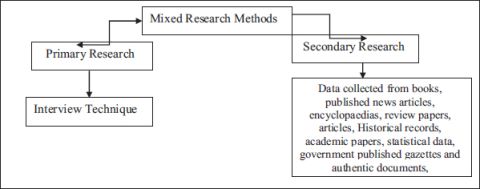

Figure 4. The Original Kota Doriya Mark Made on Handloom.

A woven Kota Doriya mark was woven into the pallu of the sari along with the name of the weaver as a trademark of the original Kota Doria (refer to Figure 4). This mark distinguished the fake Kota saris from the original ones. It was very important to let the consumers know the difference between the handloom and powerloom products.

The powerloom cannot bring back the shuttle to seal the fine motifs; instead, the shuttle goes full length to make the motif and leaves long floats in-between motifs which is visible from the back side of the fabric. These long floats are later cut off with the help of machines which makes the motif prone to fraying. Fabric glue is used to stick the loose yarns together from the backside. This causes not only a lot of inconvenience to the wearer but also the yarns used in the motifs come off easily.

Therefore original Kota fabrics can be easily differentiated from the 'fake' Kota fabrics which are made from polyester yarns and on the powerloom. A simple technique to identify is to check the back side of the fabrics. The powerloom-made Kota has long floats at the back or they have lots of cut threads at the back. Apart from these two simple techniques to check an original Kota, the drape and beauty of an original Kota fabric cannot be matched by a synthetic or powerloom-made Kota fabric. If awareness of Kota is created then any common consumer will be able to identify the original Kota fabric very easily.

A handloom woven motif in contrast is neatly tucked from both the front and the back side of the fabric. Table 2 shows the list of some of the local terminologies used in Kota Doriya weaving.

Table 2. List of Some of the Local Weaving Terminologies Used in Kota Doriya Weaving.

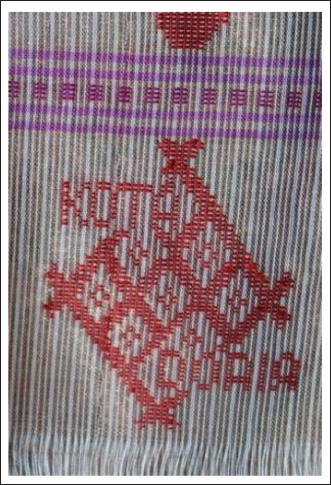

Figure 5. Smt. Hasina Begum Explaining the Kota Weaving on the Jala Loom During the Interview with Mr Nasiruddin Ansari.

The Kota Doria is one of the finest handloom woven fabrics found in India. In the hot climate of the region, this fabric provides a cool and airy feel to the wearer. The mixture of cotton and silk makes Kota fabric both strong, soft and lustrous. The base Kota fabric is often ornamented with colourful floral patterns and butis. Currently, Kota fabrics are also used as garments, handbags, home furnishings, window coverings and delicate lampshades. Kota saris are woven on the pit looms using the throw shuttle technique with Jala designs. Jala is a technique to create intricate extra weft designs on fabrics without the jacquard attachments.

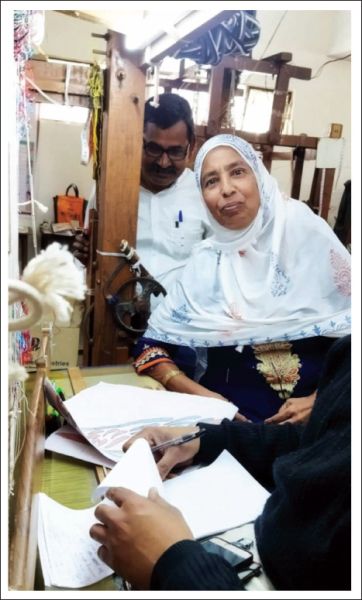

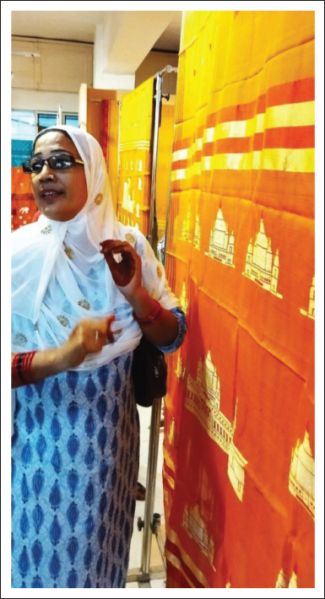

Figure 6. (left). Smt. Badrunisha Showing the Original Kota Woven Sari with Architectural Motifs on Display in the Design Studio.

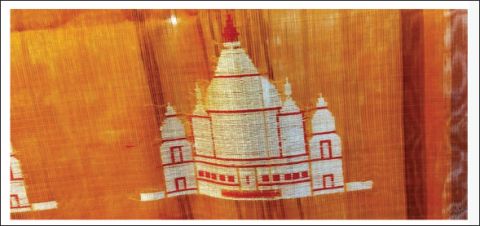

As an innovation in Kota fabric, designers developed new motifs taking inspiration from Rajasthani palace and fort architectures. Thus architectural motifs can often be seen on Kota fabrics.

This inspiration for architectural motifs can be traced back to the Baluchari saris of Vishnupur, West Bengal which is famous for making architectural patterns on pure silk brocade Baluchari saris. Baluchari saris from Vishnupur are also a GI product.

Baluchari saris have motifs inspired by the temple architecture. Kota saris took inspiration from Baluchari saris and have developed new motifs from Rajasthani palace and fort architecture. Figure 5 shows Smt. Hasina Begum explaining the Kota weaving on the Jala Loom during the interview with Mr Nasiruddin Ansari. Figure 6 shows Smt. Badrunisha shows the original Kota woven sari with architectural motifs (Figure 7) on display in the Weavers Service Design Studio, Jaipur.

Figure 7. Close-up of the Architectural Motif Woven on the Sari Pallu.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

From the above results, it is clear that Kota still has a lot of market desirability.

Conclusion

Through this study, it was learnt that Kota Doriya has a magnificent history of woven structures. Traditional weavers have propagated that the exquisite checkered-weave of Kota has its roots in the former kingdom of Mysore. It is a common folklore that a Mughal Army General, Rao Ram Singh, helped in the migration of the Kota weavers in the 17th century. Kota is also known as Kota Masuriya due to its resemblance to the locally grown masoor lentil.

This research elucidates the structure of Kota which is made of tiny squares. Each tiny square, known as Khat, on the Kota fabric contains a total of 14 yarns. Out of these 14 yarns, eight yarns are made of cotton, and six yarns are made of silk. This specific combination of yarns imparts an unmatched sheen, softness and strength to the Kota fabric. Silk yarns lend it sheen and strength whereas the softness is got from the cotton yarns. The Kota fabric is often used along with pure gold or silver zari to add gorgeous shimmer to the fabric. Other methods of value-adding on a Kota are through traditional methods of block printing or tie and dye techniques. Due to the structure and composition of the Kota fabric, it is ideal for the Indian summers.

Currently, many designers are working on enhancing the charm of this traditional handloom fabric with modern design techniques and aesthetic sense to combine the old and the new.

However, it is the timely intervention from the government of Rajasthan that has ultimately helped in reviving the falling craft to a great extent. As mentioned in the study, Mr Ashwini Saxena, Chief Executive Officer at JSW Foundation, started the act of reviving Kota and proposed GI recognition for Kota Doriya during Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s Government (1999–2004). When the erstwhile chief minister of Rajasthan Ms Vasundhara Raje Sindhia came to power she widely promoted Kota Doria saris nationally and internationally which had greatly benefitted the Kota weavers. These efforts helped the Kota handloom fabric to become a brand the world over. The unique structure of Kota Doriya encouraged the Kota Doria Development Hadauti Foundation (KDHF) to file for the GI mark with the help of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) Kota Doriya was granted the GI mark on 5th July 2005 under the Geographical Registration Act 1999.

Further efforts are required by the consumers to buy original Kota fabrics which can be easily differentiated from the 'fake' Kota fabrics which are made from polyester yarns and on the powerloom. A simple technique to identify is to check the back side of the fabrics. The powerloom-made Kota has long floats at the back and they have cut threads at the back. Apart from these two simple techniques to check an original Kota, the drape and beauty of an original Kota fabric cannot be matched by a synthetic or powerloom-made Kota fabric. If awareness of Kota is created then any common consumer will be able to identify the original Kota fabric very easily to revive the craft and bring back the lost glory of these fabled fabrics.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Chaudhary, K. (2016, April). Value addition of the Kota Doria through designing techniques. International Journal of Textile and Fashion Technology, 6(2), 2250–2378. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329091395

Hada, J. S., & Kumar, I. (2014). Hand crafted elegance Kota Doria. Fiber2Fashion.

Luniya, V., & Agarwal, S. (2012). Traditional Kota Doria saris—An innovative allure. Asian Journal of Home Science, 7(1), 10–13. https://researchjournal.co.in/upload/assignments/7_10-13.pdf

Rana, A. H. (2020). Fusing traditional techniques: Sustaining and reinventing traditional textiles. AICTE sponsored international E-conference. Enhanced Research Publication, India.

Robertson, A. F. (1950). Air porosity of open-weave fabrics* part I: Metallic meshes. SAGE Journals, 20(12). https://doi.org/10.1177/004051755002001203

Sanadhya, G., & Rehman, N. (2016). Income generation methods and saving pattern adopted by Women entrepreneurs of Kota district. The Journal of Rural and Agricultural Research, 16(1), 21–24. https://jraragra.in/Journals/2016Vol1/vol6.pdf

Tariq, S. (2022, December). Fabric weaves. https://sewguide.com/fabric-weaving-types/:https://sewguide.com/fabric-weaving-types/

vintagefashionguild. (2012, July 8). Lightest open weave or sheer fabrics. vintagefashionguild. org:https://vintagefashionguild.org/lightest-open-weave-or-sheer-fabrics/