1 Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi, Delhi, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Climate change, and especially, ‘climate deterioration’ is an alarming situation for the global scenario, and thus, the need for developing financial services and products that aim to reduce the effects of these changes is the need of the hour. This long-felt need has given birth to a new form of investing, known as green finance or broadly, sustainable finance. So, it can be said that green finance is a subset under the larger umbrella of the concept of sustainable finance. This article tries to bring to the knowledge of the readers the basic understanding of the concept of green finance, its various instruments available globally and its developments at the global and Indian level, highlighting the three stages of green finance’s evolution and its major theories. Further, it reveals the global presence of major green finance instruments like green bonds and its types, green mutual funds (MFs) and green stock exchanges. The article also deals with the concepts of emissions trading system and European Union’s Carbon Border Tax. The discussion becomes more specific in the subsequent sections, drawing the present picture of green finance concerning the Indian scenario—its green bank, green bonds, green MF and green stock exchange. Reserve Bank of India’s recent guidelines regarding green finance and India’s presidency at the last held G20 summit are also discussed, finally concluding with mapping the road ahead for India.

Green finance, green bond, sustainable finance, renewable energy, carbon tax, Paris agreement

Introduction

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) states that the meaning of green finance ‘is to increase the level of financial flows (from banking, micro-credit, insurance and investment) from the public, private and not-for-profit sectors to sustainable development priorities’. Thus, the term ‘green finance’ points to the whole gamut of products, services, instruments, etc. that help to counter the harmful effects of the dangerous industrial practices which lead to climate change and its depletion. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Wire, 2021) had suggested in its report that it published in 2018 that such a transition to a zero-carbon or a low-carbon economy requires funding of around US$2.4 trillion by the year 2030 (Diaz-Rainey et al., 2023).

The conversation around the topic began as early as 1991 but at that time, it could not find its place neither in the academic nor in the industrial world. The concept underwent many drastic changes from 1991 till date, which will be discussed further in the paper. The evolution of green finance can be tracked back to 1992 when UNEP Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) was thought of with an aim to encourage sustainable practices globally.

The whole journey of green finance can be understood with the help of three main stages (Yu et al., 2021):

Figure 1. Three Ps of Green Finance.

Further, the concept of green finance can be explained with the aid of its three Ps as shown in figure 1 (Yu et al., 2021):

The article has six sections, including the present one. The next section presents the theories of sustainable finance in brief. Following that, the article deals with the evolution of global green finance. Subsequently, sections examine major global green finance instruments globally and at the Indian level, respectively. Finally, the last section concludes with an outline of India’s future path in this direction.

Theories of Sustainable Finance: Brief Overview

Ozili (2023) has identified six major theories of sustainable finance, which also encompasses green finance. So, it can be said that these theories apply to green finance too. The paper discusses those theories in brief.

Priority Theory

This theory states that the priority that the economic agents give to sustainable finance is represented by the rate at which they try to meet the sustainable development goals (SDGs) or broadly, sustainable finance goals in a particular country or a region. This prioritisation can lead to loss of focus and resources for other goals of the economic agents—leading to a trade-off among different goals.

Peer Emulation Theory

This theory argues that in the absence of any set guidelines or standards for achieving sustainability, the economic agents tend to follow the footsteps of their peer economic agents whom they admire—these agents will undertake some of the activities since their peers are doing/have done so.

Life Span Theory

This theory is derived from Vernon’s product life cycle theory. This theory states that economic agents understand the products, services, policies and other instruments of sustainable finance have a definite product life cycle like that of other products encompassing introduction, growth, maturity and decline. This knowledge that is possessed by these economic agents enables them to better implement various sustainable finance products, services and instruments—regarding the decision as to whether to make a short-term, medium-term or long-term commitment to those products.

System Disruption Theory

This theory argues that the pursue of sustainable finance goals by the economic agents may hamper with the mainstream or traditional financial system of an economy and thus, may lead to the disruption of the businesses dependent on the traditional financing system.

Positive Signalling Theory

This theory postulates that the economic agents have an inducement to reveal positive information regarding their commitment and determination to pursue single or multiple sustainable financial goals, to those external agencies or entities who could support them in achieving their goals, either by making a public announcement or by publishing such information in their published annual reports.

Resource Theory

This theory proposes that the reasons for the difference in the advancement of different countries in the achievement of their sustainable finance goals depends on the differences in their human-made resources who are competent enough to support the attainment of such goals.

Evolution of Global Green Finance

The foundation of the UNEP FI and the draft of ‘Convention on Biological Diversity’ at the Earth Summit (took place at Rio de Janeiro) were laid around about the same time—in the year 1992. As the UNEP FI gained momentum and engaged more participants, it laid the foundation of Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997 and Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in 2005.

The GRI is an international-level institution that is headquartered at Amsterdam, the Netherlands, which encourages various organisations, businesses and governments, etc. to report the impacts generated by them on the climate, human rights, etc. On the contrary, PRI includes six principles that are abided by more than 5,000 signatories (as of 2022). These principles relate to incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) into their decision-making process and making appropriate ESG disclosures, while working in harmony with each other to facilitate the implementation of the principles. Additionally, in 2012, the Principles for Sustainable Insurance were laid down by the UN in collaboration with the insurance industry.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The SDGs are 17 global goals that were adopted by the UN in the year 2015. These 17 SDGs focus on 169 targets and are accompanied by 304 indicators. They are proposed to be achieved by the year 2030 and have stated their aim as ‘Transforming the world’. Abundant Earth Foundation, an organization supporting grassroot projects aimed at betterment of the climate, society, and the world at large, has divided the seventeen sustainable development goals into six groups which can be seen from figure 2:

Paris Agreement on Climate Change

Paris Agreement on climate change, that was entered into by 196 parties at 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in 2015, forms the most important and prominent reference point whenever green finance or any action for climate change is discussed, acting as a landmark treaty.

It is a legally enforcing international-level agreement that targets to maintain the increase in the average temperature at the global well less than 2__degreesignC as compared to the pre-industrial levels, preferably less than 1.5__degreesign. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) form a very important aspect of the Paris Agreement. NDCs refer to the communications made by the individual countries as to their commitments and the actions that they would be taking up to meet the goals enlisted in the Paris Agreement and to become resilient enough to adapt to the impacts of climate change. The agreement has listed that every nation shall provide its updated NDCs every five years.

Figure 2. Groups of SDGs.

Source: Abundant Earth Foundation.

Green Finance Instruments: Global Presence

The major instruments for mobilising green finance are green bonds, green loans, green mutual funds (MFs) and other green investment funds, sustainability-linked loans, green stock exchanges, etc.

Green Bonds

These are the bonds, whose proceeds are directed to finance or refinance green projects that is, those projects which are involved in green activities like renewable energy generation, carbon emission and the like. The first ever green bond was rolled out in the year 2007 by the European Investment Bank (EIB) (Bhutta et al., 2022). It was called ‘Climate Awareness Bond (CAB)’ with a focus on renewable energy activities, or specifically, energy efficiency. The proceeds of this bond are still used to help support activities that focus on climate change mitigation. The CABs were extended to lending activities that went beyond its major focus for the first time in the year 2020 (EIB) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). Since then, various green bonds at sovereign, municipal and firm level have been issued with the first sovereign green bond (SGrBs) issued by Poland in 2016.

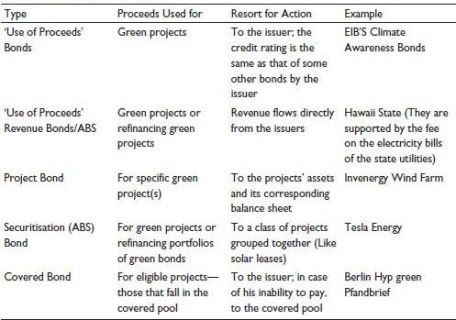

Types of Green Bonds.Table 1 attempts to explain the various types of green bonds that can be issued by an entity (CBI):

Labelled vs. Unlabelled Green Bonds (Hyun et al., 2021). Green bonds may be categorised as labelled or unlabelled—labelled green bonds being the ones that have received a third-party certification, rendering them to be more authenticate and credible. Labelled green bonds can be said as the ones complying with the Green Bond Principles (GBP). Thus, GBP can be considered as a gold standard for the certification of green bonds. Many studies have shown that a green label does have a substantial impact on the investors as they consider green labelled bonds to be less risky for the environment and, also such a label or an assessment is considered to lower the information costs for them, as they are supposed to have undergone due diligence. It has been found that the issuers of green bonds enjoy a comparative convenience as compared to the issuers of traditional bonds (Gianfrate & Peri, 2019).

Major Green Bond Issuances Globally. The global market for green finance showed remarkable growth since the year 2014. Going by the data published by the Climate Bonds Initiative in its report of November 2022, the total green bond issuances crossed US$2 trillion, as on 30 September 2022. European countries have proved to be the top issuers of SGrBs with 5 years as well as 10-year time periods emerging as the most preferred ones (Manglunia, 2023). Globally, the total green bond issuances have reached US$2.5 trillion, as of January 2023, according to a report published by the World Bank in April 2023.

Table 1. Kinds of Green Bonds.

Recently, in September 2023, an initiative led by Inter-American-Development Bank (IDB), in collaboration with various bilateral and multi-national institutions, has been made to make this platform global. The aim of this initiative was to enhance the quality of data and increase transparency in the green bond market.

Green MFs

Green MFs or impact-investing funds are those MFs that strive to contribute to the society by investing in companies considered as socially or environmentally responsible. It can include such funds that are always looking out for those corporates which work towards energy consumption reduction, valuing and building relationship with various stakeholders, etc. According to Stevens (2020), the quantity of both, such ESG-focused funds and the total asset amount invested in these types of funds, have nearly doubled in the previous three years.

Do Such Funds Perform Well? Many studies have attempted to find out whether such funds fulfil their promise of working towards a carbon-neutral economy. A study performed by Ji et al. (2021) in the context of BRICS nations has showed that green funds have outperformed their counterparts. The study has also proved Chinese green funds performing the best among all the others.

Green Stock Exchanges

Green stock exchanges are basically those stock exchanges which deal only with green securities. The Luxembourg Green Exchange (LuxSE), established in 2016, has emerged as the world’s first stock exchange platform focusing only on sustainable securities (United Nations Climate Change, 2023). The main objective of it is to inject sustainable capital into the world economy and to redirect money towards sustainable projects.

The LuxSE has partnered with prominent institutions in the countries of Africa, South America and Asia to help promote the agenda of sustainable finance and, to strengthen international collaborations for sustainable development. Another similar platform is the ‘Green Bond Transparency Platform’. It is an innovative platform that was brought into existence by the IDB. Its aim was to increase clarity regarding the green bond markets situated in Latin America and in the Caribbean. It is a free and public platform to harmonise and standardise the reporting of the green bond market.

Emissions Trading System (ETS) (Peng et al., 2018)

An ETS, or an emission trading system, is one of the mechanisms of implementing carbon pricing. Such a system puts a cap either on the total amount of emissions, or on the emission intensity, which is measured as emissions for each unit of a country’s GDP. It may include emissions from all or some of the greenhouse gases, like CO2. Governments of the countries then provide the companies with allowances, mostly in the primary market1, of an amount equal to the amount of cap. Firms then trade these allowances in the secondary market2. Thus, in this way, the emission reduction is achieved at a very low cost.

Many leading economies and institutions have set up their emission trading systems. The EU ETS, which is world’s first such system, was set up in the year 2005. It is currently in its fourth phase (2021–2030). The system has pledged to adopt many legislative proposals, chalking out its plan to attain climate neutrality by the year 2050, with an intermediate target to achieve a minimum 55% net reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases by 2030. Over these years, it has emerged successful in establishing a carbon price, free trading of emissions across the EU and ultimately including more gases under its ambit. Currently, the allowances are set at around US$95 (€90) per ton. Other prominent ETSs across the globe include the ones in China, California, Switzerland and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

EU’s Carbon Border Tax (CBAM)

The CBAM or the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a carbon leakage instrument, or simply, a carbon tax. Its preliminary deal was entered into on 13th December 2022, and it was decided to be implemented on imported goods of seven main carbon-intensive categories—iron, steel, cement, aluminium, fertiliser, hydrogen and electricity. It was decided to implement its initial phase w.e.f. 1st October 2023, and will be phased in full w.e.f. 1st January 2026 (Cheema, 2023).

During this transitional period, traders will be required to give reporting of the emissions contained in the goods imported by them, without having to make any compensatory payment. This mechanism will pave way to adjust by 2026. Ultimately, on 1st January 2026, those EU businesses that import goods covered by CBAM will have to purchase certificates. This CBAM mechanism will thus make sure that the carbon price of the imports becomes equivalent to the carbon price of the locally produced goods on the assumption that the primary aim of the EU, which is related to climate is not compromised by payment of some fee to compensate for the embedded carbon emissions produced by the overseas producers, generated during the production of some specific goods imported by EU countries. Ultimately, the carbon leakage between non-EU and EU goods is avoided (European Commission, 2023).

The CBAM takes into coverage only around 3% (Gros, 2023) of the imports of the entire EU, totalling around €50–60 billion annually. In this way, CBAM will remain only a minor irritant for most countries. It was estimated that CBAM will cover around 80 million tons of direct emission of CO2, implying a revenue of around €7.2 billion (at €90/ton ETS price). This revenue would be directly routed to (Gros, 2023) the budget of EU.

Current Landscape of Green Finance in India

India took the first-ever global step in the direction of green finance by ratifying the International Solar Alliance (ISA) agreement with France on 1st December 2015 with an aim to provide a dedicated and specialised platform for cooperation of countries rich in solar-resource. ISA attempts to develop economic energy solutions brought into action by solar energy so that low-carbon growth can be achieved. Before that, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy was setup in the year 2006 to enhance research and development, protect intellectual property and ultimately promote sources of renewable energy. Also, in 2008, the National Action Plan on Climate Change was launched. It consists of eight national-level missions with an aim to bring a reduction in the emission intensity, increase the forest cover, improve energy efficiency and ultimately inculcate sustainable habits.

India submitted its first NDCs to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) on 2nd October 2015. As of August 2022, India has submitted its updated NDCs to UNFCCC to exhibit its contribution and steps to mitigate climate change with three major updates, for the period up to the year 2030 (Bansal, 2022):

Green Bank

India converted Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA), which is a non-banking financial institution, to a green bank in the year 2016. Green Bank points to any organisation financing pro-environment activities and aiming to effectively lessen carbon emissions taking the help of banking activities. IREDA’s primary aim was thus to boost green energy and to help mobilise funds from private sector for the same. Post that, many banks like SBI, Union Bank, ICICI Bank, etc., have been providing necessary and adequate financing for undertaking green projects.

Green Bonds

The first ever green bonds were launched in India in 2015 by YES Bank. Post that, in 2017, IREDA launched its 5 year green bonds which were called ‘Green Masala Bonds’, which became the first ones to get listed in the International Securities Market. India had issued approximately US$6.11 billion worth of green bonds within 11 months of the year 2021. India trails behind the US and China only with regards to its green bond issuances.

Ms Nirmala Sitharaman, who is the union minister for corporate affairs and finance, had announced on 1st February 2022 about the government’s plan to issue SGrBs (Manglunia, 2023). The funds of the same would be utilised in public sectors contributing towards reduction of carbon intensity. Finally, the first tranche of the bonds was issued on 25th January 2023. The issue was worth ` 80 billion, or $980 million worth of 5-year and 10-year green bonds. Subsequently, the government announced on 9th February 2023 to issue subsequent tranche of SGrBs worth ` 80 billion (Hussain & Dill, 2023). A Green Finance Working Committee was constituted by the Ministry of Finance. It is supposed to meet twice a year to help and guide the ministry in the selection of appropriate green projects.

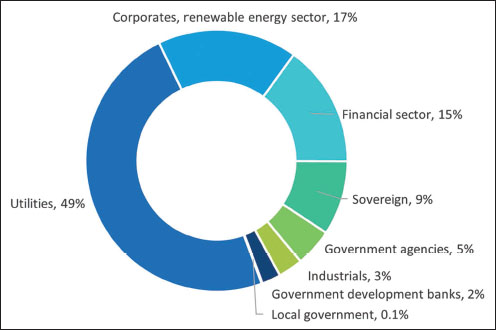

Figure 3 clearly shows that the utilities sector issues approximately half of the cumulative green bond proceeds issued. The other half consists of sectors like corporates, financial sector, sovereign and government agencies.

India’s largest green bond issuer is Greenko Group. It is engaged in financing wind, solar and hydropower projects in numerous states of India taking help of green bond proceeds. Apart from private and sovereign level, Ghaziabad Nagar Nigam became the first Indian body in 2021 to issue municipal green bonds, equivalent to US$20 million. This action was then followed by Indore Municipal Corporation in 2023 which issued green bonds equal to US$87 million (Hussain & Dill, 2023).

Figure 3. Amount of Green Bond Issued in India by Various Issuers.

Source: World Bank with data extracted from Bloomberg.

Green Mutual Funds (MFs)

In the Indian context, ESG MFs are categorised as thematic equity funds. These funds are focusing on meeting the environmental, social and corporate governance standards, and gaining profit by adopting ethical means of practice. SBI MF, ICICI MF, Axis MF and Kotak MF are some of the MF companies which have launched these thematic MFs in the recent years (ZeeBiz Webteam, 2023).

Apart ESG funds, India has also witnessed launch of green energy funds. These are those funds that sought to invest in companies which operate in green energy and similar resources sectors, aiming at those corporates engaged in generating energy from wind, hydro and solar sectors. Two major green energy MFs in India are those of DSP MF and Tata MF (Devi, 2023). These MFs are engaged in those equity and related companies which are involved in discovering, developing, producing and distributing natural resources. They give emphasis to renewable energy, energy storage and moreover, to enabling energy technologies.

Recently, in March 2023, HDFC MF becomes the first asset management company which filed for the country’s first SGrBs MF (Live Mint, 2023). The MF is seeking to combine SGrBs with Target Maturity Funds (TMFs), an innovative debt instrument. TMFs are open-ended and passive instruments that aim to duplicate the composition of some predetermined fixed-income index fund. They have a fixed maturity date. The HDFC MFs’ are planned to be called HDFC Nifty India SGrBs January 2033 Index Fund and HDFC Nifty India SGrBs January 2028 Index Fund.

Green Stock Exchange

Many Indian green companies are now being traded on Indian stock exchanges—the Bombay Stock Exchange, plus, the National Stock Exchange (NSE). They include well-reputed companies such as Adani Green, Suzlon Energy, ION Exchange and Praj industries, among others. In February 2023, NSE finally got the consent of Securities and Exchange Board of India to establish a Social Stock Exchange (SSE) (The Economic Times, 2023a). SSE is a type of fund-raising platform which is specially created for social businesses to help them access various types of donations. The listing of SSE works like a traditional initial public offer. But, instead of the shares, the allotment of Zero Coupon Zero Principal instruments is done to the participants. Also, no returns are yielded on such instruments.

Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Directions Aimed at Green Finance

In February 2023, RBI governor Shaktikanta Das announced some regulatory initiatives to promote sustainable finance in the country. The guidelines have been draughted for Regulated Entities, which include some banks, some primary co-operative banks, few non-banking financial companies, credit information companies and some institutions like NaBFID, the Exim Bank, NABARD, the National Housing Bank and the Small Industries Development Bank of India.

The guidelines consist of (Perumal, 2023; The Economic Times, 2023b):

Banks must fulfil some conditions to enable them to accept green deposits from investors:

These green deposits are meant to be used to promote renewable energy, climate change adaptation, clean transportation, sustainable waste management and promoting sustainable management of natural resources. On the contrary, it will exclude those projects which are engaged in extracting, distributing and producing fossil fuels, including their improvements or upgrades, or in those projects in which the main energy source is nuclear power generation, tobacco, weapons or renewable energy projects that generate biomass energy using feedstock which originates from preserved areas, landfill projects or those hydropower plants that are bigger than 25 MW (Singh, 2023).

The RBI further announced in February 2023 to launch a dedicated page on its own website for consolidated all directions, speeches, press releases and publications made by RBI related to climate risk and sustainable finance.

India’s G20 Presidency

India recently got the first-ever chance to hold the 18th G20 summit held during 9–10th September 2023. The summit was held in New Delhi, the capital city of the country and was themed ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (One Earth—One Family—One Future). The aim of the summit was to attain unanimity in addressing global challenges effectively (Sharma, 2023).

The summit was successful in achieving a unanimous approval, a 100% consensus in signing G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration. This declaration highlighted the Ukraine conflict and its following economic implications, a concrete path to regulate cryptocurrencies, strengthening and boosting multi-lateral development banks and the placement of a digital and public infrastructure for bettering financial inclusion.

Apart from this, the declaration emphasised the need to mobilise approximately US$5.8–5.9 trillion for developing countries in the period before 2030, and moreover, US$4 trillion each year aimed at clean energy technologies by the year 2030. All this needs to be performed to achieve net-zero emissions by the year 2050. Moreover, the African Union, that represents 55 nations in the African content was granted full membership of the G20. Additionally, a Memorandum of Understanding was ratified among the leaderships of various nations including India, Saudi Arabia, the US, Germany, France, the UAE, Italy and the European Union for the setting up of the India–Middle East–Europe economic corridor. This envisioned corridor is set to be a transportation route consisting of sea lanes and railways, to promote relations and trade between Asia, Europe and the Arabian Gulf.

Lastly, the newly signed New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration witnessed commitments to focus on LiFE, reaffirming the steps to attain SDGs and, to witness the launch of the Global Biofuel Alliance, an organisation focused on promoting adoption and development of sustainable biofuels, blended with the establishment of relevant certifications and standards.

What Lies Ahead for India?

Green finance is clearly gaining momentum in India. There have been major improvements in the financing options available to the public, and in public awareness at the same time. But many challenges still exist to implement green finance in a developing economy like India. The main challenges include that of greenwashing, lack of proper and sufficient knowledge (Soundarrajan & Vivek, 2016; Wasan et al., 2024) plurality of definitions of green finance, information asymmetry (Ghosh et al., 2021) and high borrowing costs.

Although the nation has taken considerable steps around green finance and is only third in the issuances of green bonds, India still has a long path to walk on. We strongly believe that a successful integration and coordination between better and more financial products, competitive tax regime and increased public awareness and understanding is required for making green investment reach its desired destination to meet the net-zero emissions and other targets set by the competent authorities globally.

Achieving green finance in a comprehensive fashion is not something that is difficult for an emerging economy like India. It is quite easily achievable with an adhesive cooperation among various policymakers, private and public enterprises and the investment community at large.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Notes

Bansal, A. (2022). Green financing in India—Need, significance, urgency, and way forward. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.in/sustainability/article/opinion-green-financing-in-india-need-significance-urgency-and-way-forward/articleshow/92948265.cms

Bhutta, U. S., Tariq, A., Farrukh, M., Raza, A., & Iqbal, M. K. (2022). Green bonds for sustainable development: Review of literature on development and impact of green bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121378

Cheema, J. (2023). EU’s CBAM: Taxing trade for transition amid global climate concerns. Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/economy/news/eu-s-cbam-taxing-trade-for-transition-amid-global-climate-concerns-123101101200_1.html

Cortellini, G., & Panetta, I. C. (2021). Green bond: A systematic literature review for future research agendas. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(12), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14120589

Devi, N. (2023). 2 Green energy mutual funds in 2023. Ticker Tape. https://www.tickertape.in/blog/green-energy-mutual-funds/#:~:text=The%20investment%20objective%20of%20DSP,distribution%20of%20natural%20resources%20etc.

Diaz-Rainey, I., Corfee-Morlot, J., Volz, U., & Caldecott, B. (2023). Green finance in Asia: Challenges, policies and avenues for research. Climate Policy, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2168359

European Commission. (2023). Carbon border adjustment mechanism. European Commission. https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/green-taxation-0_en

Ghosh, S., Nath, S., & Ranjan, A. (2021). Green finance in India?: Progress and challenges. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352030007_Green_Finance_in_India_

Scope_and_Challenges

Gianfrate, G., & Peri, M. (2019). The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.022

Gros, D. (2023). EU carbon border tax makes economic sense. The Asset. https://www.theasset.com/article-esg/50185/eu-carbon-border-tax-makes-economic-sense

Hussain, I. F., & Dill, H. (2023). India incorporates green bonds into its climate finance strategy. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/climatechange/india-

incorporates-green-bonds-its-climate-finance-strategy

Hyun, S., Park, D., & Tian, S. (2021). Pricing of green labeling: A comparison of labeled and unlabeled green bonds. Finance Research Letters, 41, 101816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101816

Ji, X., Zhang, Y., Mirza, N., Umar, M., & Rizvi, S. K. A. (2021). The impact of carbon neutrality on the investment performance: Evidence from the equity mutual funds in BRICS. Journal of Environmental Management, 297, 113228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113228

Live Mint. (2023). HDFC mutual fund files for India’s first sovereign green bond MF. Live Mint. https://www.livemint.com/mutual-fund/mf-news/hdfc-mutual-fund-files-for-india-s-first-sovereign-green-bond-mf-11679644665363.html

Manglunia, A. (2023). Unlocking full potential of green bonds in India. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/bonds/unlocking-full-potential-

of-green-bonds-in-india/articleshow/101541808.cms?from=mdr

Ozili, P. K. (2023). Theories of sustainable finance. Managing Global Transitions, 21(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.26493/1854-6935.21.5-22

Peng, H., Feng, T., & Zhou, C. (2018). International experiences in the development of green finance. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 8(2), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2018.82024

Perumal, J. P. (2023). What are RBI regulations on green deposits? The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/explained-what-are-rbi-regulations-on-green-deposits/article66866265.ece

Sharma, H. (2023). Key outcomes of the 2023 G20 Summit held in India. India Briefing. https://www.india-briefing.com/news/key-outcomes-of-the-2023-g20-summit-held-in-india-29483.html/

Singh, V. (2023). Driving sustainability: RBI paves the way for green finance with new framework for acceptance of green deposits. ESG BROADCAST. https://esgbroadcast.com/rbi/driving-sustainability-rbi-paves-the-way-for-green-finance-with-new-

framework-for-acceptance-of-green-deposits/

Soundarrajan, P., & Vivek, N. (2016). Green finance for sustainable green economic growth in India. Agricultural Economics (Czech Republic), 62(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.17221/174/2014-AGRICECON

Stevens, P. (2020). ESG index funds hit $250 billion as pandemic accelerates impact investing boom. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/02/esg-index-funds-hit-250-billion-as-us-investor-role-in-boom-grows.html

Sunlegal, P. K. (2022). India: Green finance: Exploring the Indian financial system. https://events.development.asia/system/files/materials/2019/11/201911-accelerating-sdg-

implementation-

The Economic Times. (2023a). NSE gets nod to launch social stock exchanges. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/nse-gets-final-nod-from-sebi-to-launch-social-stock-exchange/articleshow/98174411.cms?from=mdr

The Economic Times. (2023b). RBI announces regulatory guidelines on climate risk and sustainable finance. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/rbi-announces-regulatory-guidelines-on-climate-risk-and-sustainable-finance-for-res/

United Nations Climate Change. (2023). Luxembourg green exchange. https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/financing-for-climate-friendly-investment/luxembourg-green-exchange

Wasan, P., Kumar, A., & Luthra, S. (2024). Green finance barriers and solution strategies for emerging economies: The case of India. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2021.3123185

Wire, S. (2021). What is green finance? Lloyds Banking Group. https://www.lloydsbankinggroup.com/insights/green-finance.html

Yu, X., Mao, Y., Huang, D., Sun, Z., & Li, T. (2021). Mapping global research on green finance from 1989 to 2020: A bibliometric study. Advances in Civil Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9934004

ZeeBiz Webteam. (2023). World Environment Day 2023 a look at top ESG funds in India. ZeeBusiness. https://www.zeebiz.com/personal-finance/mutual-fund/news-world-environment-day-2023-a-look-at-top-esg-funds-in-india-stst-238496