1Department of Operations Management, Faculty of Management, University of Peradeniya, Central Province, Sri Lanka

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://wwwcreativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Globally, grassroots entrepreneurship is increasingly recognised for its capacity to foster innovation and resilience in resource-scarce environments. Particularly in the Global South, entrepreneurs often operate informally, drawing on local knowledge, social networks and improvisation to overcome systemic constraints. However, scholarly understanding of how these practices manifest in non-urban South Asian contexts remains limited. In Sri Lanka, such informal entrepreneurial efforts play a crucial role in bridging service gaps, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas. Despite limited institutional support, many individuals initiate ventures by creatively mobilising resources, yet their stories remain underexplored. This study investigates the case of Saranga Lakruwan, an entrepreneur from Laxapana, who transformed a modest vehicle modification project into Ever Rich, a growing customisation enterprise in Ginigathena. Largely self-taught, Saranga leveraged informal training, personal networks and resource bricolage to offer tailored vehicle interior modifications. Using a qualitative case study approach, data were gathered through semi-structured interviews, observations and archival materials. Thematic analysis revealed nine key themes: making do, informal skill acquisition, improvisation, bootstrapping, customer-centred innovation, grassroots design, niche market creation, social responsibility and digital visibility and grassroots marketing. The findings illustrate how entrepreneurial bricolage and grassroots innovation enable business development and community engagement in informal economies. Saranga’s case contributes to broader understandings of how entrepreneurs in emerging markets construct economic and social value despite material constraints, offering insight into locally embedded, bottom-up innovation strategies.

Entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial bricolage, grassroots innovation, Sri Lanka, micro-enterprises, vehicle customisation, resource mobilisation, social value creation

Introduction

Entrepreneurship plays a central role in economic and social development, particularly in developing countries where formal employment opportunities remain limited. It is increasingly recognised that not all entrepreneurs follow formal, well-resourced or high-tech pathways to success. Instead, many individuals in constrained environments adopt creative, hands-on approaches that rely on available resources, local knowledge and incremental innovation. This phenomenon is captured by the concept of entrepreneurial bricolage, which refers to ‘making do by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities’ (Baker & Nelson, 2005, p. 333).

Bricolage emphasises improvisation, adaptability and learning-by-doing—qualities often found in informal or grassroots entrepreneurial contexts. It is especially relevant in countries like Sri Lanka, where systemic barriers such as capital shortages, regulatory limitations and infrastructure gaps hinder the emergence of conventional start-ups (World Bank, 2020). Entrepreneurs operating in such environments must innovate not through formal R&D but by creatively repurposing and recombining tools, knowledge and relationships to deliver value.

Innovation, in this context, goes beyond high-tech or scientific breakthroughs. As Dhewantara and Surya (2021) argue, innovation at the grassroots level often emerges from the bottom-up, driven by necessity, localised knowledge and experimentation. In Sri Lanka, grassroots innovation manifests across sectors such as agriculture, handicrafts and micro-industries. Yet, these innovations are often invisible to national innovation systems, which continue to prioritise technology-based or export-oriented entrepreneurship (Wijesinghe & Perera, 2020). The disconnect between informal innovation practices and institutional support mechanisms contributes to what can be identified as a performance gap in the national entrepreneurship ecosystem.

This performance gap is particularly visible in sectors like informal transport customisation, where entrepreneurs add value through vehicle modifications and personalised services. While these micro-enterprises generate employment, attract demand and stimulate local supply chains, they remain largely unsupported in policy and unrecognised in innovation indices (Cooper et al., 2020). The lack of incubators, financial mechanisms or skills training tailored to such contexts limits the scalability and sustainability of these ventures. Therefore, bridging this performance gap requires a better understanding of how entrepreneurs innovate within limitations and how their practices can inform inclusive economic development strategies.

The present study investigates the entrepreneurial journey of Saranga Lakruwan, a young innovator from the Nuwara Eliya District, who transformed a single rented vehicle into a thriving automotive customisation enterprise, Ever Rich. Operating from an informal, self-taught background, he began by modifying a three-wheeler using skills learned through certificate programmes and school-based experimentation. Over time, he expanded his services to cars, vans and eventually buses, creating a niche market for customised interior solutions, including lighting, entertainment systems and structural modifications. His innovations were not driven by access to technology or capital but by bricolage, leveraging whatever tools, skills and materials were at his disposal to meet evolving customer needs.

This case thus fills an empirical gap in existing Sri Lankan entrepreneurship literature, which has largely focused on formal small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), urban start-ups and export-oriented businesses (Wickramasinghe & Wimalaratana, 2016). There is limited qualitative evidence on how grassroots entrepreneurs initiate and scale businesses using informal knowledge systems and resource-constrained innovation strategies. Moreover, from a theoretical perspective, most Sri Lankan entrepreneurship studies adopt opportunity-based or resource-based views (Alvarez & Barney, 2007), with insufficient attention to the mechanisms of improvisation, bricolage and effectuation in local enterprise development.

By applying the lens of entrepreneurial bricolage and grassroots innovation, this study seeks to understand how creative resource use, local demand recognition and informal learning pathways shape entrepreneurial outcomes. It explores the transformation of an individual idea into a sustainable enterprise and its implications for supporting innovation in under-represented entrepreneurial contexts.

Research Objectives

Case Study: From Wheels to Wealth—The Story of Saranga Lakruwan

In the misty hills of Laxapana, nestled deep within the central highlands of Sri Lanka, the story of Saranga Lakruwan begins, not with riches or formal opportunity, but with a spark of curiosity, a pair of skilled hands and an old three-wheeler. Born in 1992 into a humble family in the Nuwara Eliya District, Saranga’s early life was shaped by economic hardship but also by a nurturing environment of creativity, perseverance and integrity. His father, a simple man with a rented vehicle, became both provider and quiet role model, instilling in Saranga a work ethic that would one day lay the foundation for a unique entrepreneurial journey.

Educated at Laxapana College, Saranga stood out not for his grades alone but for his ability to apply theory to practice. Whether repairing tools or experimenting with electrical wiring at school, he developed a hands-on relationship with the material world. Though financial constraints limited access to higher education, Saranga did not stop learning. He pursued several vocational and technical certificate courses after his school years, seeking knowledge not for the sake of credentials but for practical empowerment.

The turning point came when his father allowed him to rent and operate the family’s old three-wheeler. What began as a means to earn a modest income quickly evolved into a creative endeavour. Drawing from his technical training and innate aesthetic sense, Saranga began customising the three-wheeler. He installed a stylish lighting system, upgraded the sound setup, crafted a sleek cabin design and turned a basic vehicle into a moving expression of innovation. It was an act of bricolage, combining available resources, repurposed materials and self-taught skills to create something entirely new.

This small transformation did not go unnoticed. Villagers began approaching him, requesting similar modifications for their own three-wheelers. Sensing demand, Saranga began offering vehicle customisation services to others in his community at affordable rates. What started with three-wheelers soon expanded to cars and vans. Without a formal workshop or large budget, he continued working from home—cutting wires, adjusting panels, fitting lights—all with precision, patience and ingenuity. His innovation grew alongside his reputation.

The home workshop, however, could no longer accommodate the growing stream of clients. Recognising the need for space and visibility, Saranga made a bold move to Ginigathena, near Nawalapitiya, where he opened his own vehicle modification shop, Ever Rich. It was more than just a name; it was a declaration of vision. The new location offered adequate parking space and facilities to modify up to three buses at a time. Saranga hired three workers and began scaling his operations to serve a wider clientele.

The shop quickly became known as a hub of interior vehicle innovation. From ambient lighting systems, high-performance sound installations and digital displays to customised fans, floor lighting and wall textures, Ever Rich became a one-stop solution for creative modifications. Saranga sourced parts affordably, adapted existing tools for new uses and learned on the job—hallmarks of entrepreneurial bricolage. His ability to deliver tailor-made services based on customer budgets and preferences set him apart in a highly informal market.

In an area where few believed in the market potential for vehicle customisation, Saranga not only identified a gap but built an entire service model around it. Today, modifying a single bus can earn him up to 1.5 million rupees. He sells vehicle accessories, provides advisory services to clients and continues to lead every project with hands-on involvement. His shop is the only one in the region offering such specialised services, a testament to his vision and resilience (Figure 1).

Saranga’s journey is not just about mechanical skills, it is a story of innovation born from scarcity. Without start-up capital, formal business education or institutional support, he created value through passion, learning and adaptability. He exemplifies the performance potential hidden within Sri Lanka’s informal sector and highlights the critical performance gap between entrepreneurial creativity on the ground and the support available through national policy frameworks.

Figure 1. Innovations of Ever Rich.

Source: Business’s Official Facebook Page – Ever Rich (2024).

Figure 2. Logo and Themes of Ever Rich.

Source: Business’s Official Tiktok Page – Ever Rich (2024).

Entrepreneurs like Saranga often operate in isolation from mainstream development discourse, yet they innovate, employ others and meet real market needs (Figure 2).

This case illustrates how grassroots innovation, when powered by bricolage, can drive enterprise development in unexpected ways. Saranga’s success lies in his ability to ‘make do’ with what he had and elevate it with vision. He did not wait for the perfect opportunity, he built it, wire by wire, light by light, one modified vehicle at a time. His story is a powerful reminder that entrepreneurship is not only about solving problems but about reimagining possibilities with what is already at hand.

Today, Saranga continues to innovate, expanding his services and training others. His legacy is not just a shop filled with lights and sound systems, it is a living example of how creativity, grit and grassroots ingenuity can build wealth from wheels.

Research Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative case study approach to explore how entrepreneurial bricolage and grassroots innovation shape the formation and growth of a vehicle customisation enterprise in Sri Lanka. Focusing on the lived experience of Saranga Lakruwan, the founder of Ever Rich, the research aimed to understand how an entrepreneur operating in a resource-constrained, informal environment creatively mobilised local knowledge, materials and market insights to build a successful enterprise. Given the exploratory nature of the inquiry and the focus on context-specific, in-depth understanding, an interpretivist case study design was selected.

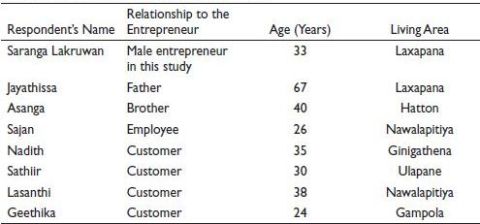

The single embedded case was chosen through purposive sampling, based on its richness in entrepreneurial bricolage practices and the unique trajectory of the entrepreneur. Saranga’s journey from a village-based, self-taught technician to a regionally recognised customiser of vehicle interiors offered a compelling context to examine how innovation emerges in informal and low-capital settings. The case is particularly relevant for understanding bottom-up entrepreneurial processes and how individuals construct new business models through experiential learning, improvisation and demand-driven adaptation (Table 1).

Data were collected using multiple qualitative methods to ensure triangulation and credibility. Primary data were obtained through semi-structured interviews with Saranga, his three employees, two family members and four long-term clients who have had their vehicles modified at Ever Rich. These interviews were conducted in Sinhala, digitally recorded, transcribed and translated into English for analysis. The interview protocol was designed to elicit insights into Saranga’s motivations, resource use, decision-making processes, innovation practices and customer engagement strategies.

Secondary data included direct observations at the workshop in Ginigathena, where the researcher documented the physical setting, types of modification tools, work practices and client interactions. Photographs of modified vehicles, the shop layout and customisation components (such as lighting systems, sound setups and interior features) were also collected. Archival materials such as marketing content, Facebook posts, digital design catalogues and certificates from training programmes were reviewed to contextualise the entrepreneur’s skills and public image.

The collected data were analysed through thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) framework. Themes were iteratively refined, compared across data sources and organised into analytical categories that answered the study’s research objectives.

The study upheld ethical research standards, including informed consent, voluntary participation and confidentiality of all participants. Pseudonyms were used where appropriate. The researcher maintained reflexive field notes to ensure positionality awareness and minimise interpretation bias.

This methodology aligns with qualitative case study guidelines advocated by Yin (2014) and Creswell (2013), which emphasise in-depth, real-world exploration of a bounded system. It is particularly suited for capturing the complexity of entrepreneurial bricolage, where linear or quantitative frameworks may fail to reflect the dynamic, iterative and experiential nature of resource mobilisation and innovation in the informal economy.

Table 1. Profile of the Respondent in This Study.

Sample Profile

Results and Discussions

This section presents the thematic analysis of the qualitative data gathered from the case study of Ever Rich, aligned with the research objectives. Thematic analysis enabled the identification of patterns and meanings within the narrative, offering rich insights into the entrepreneurial journey of Saranga Lakruwan. The themes were derived from an in-depth reading of the case and reflect core aspects of entrepreneurial bricolage and social value creation.

Research objective 1: To explore how entrepreneurial bricolage practices have been applied by a grassroots innovator to initiate and grow a vehicle customisation business in Sri Lanka.

Saranga Lakruwan’s entrepreneurial journey began with a humble mindset of ‘making do’ with limited resources. His ability to creatively use whatever was available—basic tools, recycled materials and personal skills—allowed him to start customising vehicle interiors right from home. This behaviour echoes Baker and Nelson’s (2005) concept of bricolage, where resource constraints inspire inventive reuse. Saranga described this early phase: ‘I had no fancy tools, but I focused on fixing and decorating three-wheelers using what I had sometimes just old wiring or cheap lights. It was important to make the best of little things’.

His father Jayathissa reflected on this resourcefulness: ‘Even though we had little money, Saranga’s hands could turn old parts into something valuable. That was the start of his success’.

This pragmatic approach to resource mobilisation is crucial in informal economies and highlights how grassroots entrepreneurs circumvent formal capital barriers (Baker & Nelson, 2005).

Unlike entrepreneurs who rely heavily on formal education, Saranga’s skills were forged through a combination of school education, practical certificate courses and experiential learning. This blend of formal and informal knowledge enabled him to build competence in wiring, sound systems and vehicle decoration. His employee Sajan emphasised this skill depth: ‘Saranga’s knowledge comes from both training and hands-on work. He knows exactly how to fix problems and improve designs’.

Such continuous skill-building is vital for bricolage, where entrepreneurs recombine knowledge and practices gained from diverse sources (Fisher, 2012). It also empowers entrepreneurs to adapt swiftly to emerging challenges and customer needs.

Creativity in problem-solving stands at the core of Saranga’s business model. Faced with unavailable parts or unique client requests, he improvises with alternatives, an essential trait of bricolage entrepreneurship (Garud & Karnøe, 2003). Customer Sathiir praised this flexibility: ‘When I asked for a special sound and light setup, some parts weren’t in stock, but Saranga found clever alternatives that worked perfectly’.

This adaptability illustrates how entrepreneurs turn constraints into opportunities, tailoring solutions that large firms or formal industries might overlook.

Saranga’s growth strategy was characterised by bootstrapping, reinvesting profits to scale gradually from home-based work to a formal workshop. This incremental path reflects findings from Greve and Salaff (2003), who note that small-scale entrepreneurs rely on careful, stepwise growth in resource-poor settings. Employee Sajan shared: ‘We started in a small space, but as demand increased, Saranga invested in a bigger workshop and hired staff. He never borrowed from banks but grew slowly with what he earned’ (Figure 3).

This demonstrates a sustainable growth model rooted in pragmatic financial management and gradual capacity building.

Research objective 2: To examine how informal skills, resource improvisation and localised innovation contributed to the development and differentiation of entrepreneurial services in a resource-constrained environment.

A distinguishing feature of Saranga’s venture is the close relationship with customers. He customises modifications based on individual budgets, vehicle types and preferences, reflecting a user-driven innovation process (von Hippel, 2005). Lasanthi, a private bus owner, explained: ‘Saranga customizes my buses according to route needs and passenger comfort, always adjusting based on what I can afford’.

Figure 3. Entrepreneur’s Works.

Source: Business’s Official Tiktok Page – Ever Rich (2024).

This approach strengthens client loyalty and distinguishes Ever Rich from generic vehicle workshops, illustrating how grassroots entrepreneurs tailor offerings to local demand.

Saranga’s innovations, from lighting systems to fan placements and sound enhancements, are contextually embedded and arise from his understanding of local needs. Nadith, a fellow entrepreneur and customer, emphasised the uniqueness: ‘Saranga combines style with affordability, creating designs that look modern but fit local budgets’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Customised Products.

Source: Business’s Official Facebook Page – Ever Rich (2024).

This localised innovation is critical for informal sectors where imported or mass-market solutions do not fully meet customer expectations (Seyfang & Smith, 2007).

In a region with no other vehicle interior customisation shops, Saranga identified and exploited a market niche. Customer Sathiir remarked: ‘Here, no one else does what Saranga does. If you want your vehicle personalized, you come to him’.

This ability to create and dominate a niche aligns with entrepreneurial theories on opportunity recognition in informal markets (Greve & Salaff, 2003). It highlights how grassroots entrepreneurs fill service gaps through innovation and local knowledge.

Beyond business, Saranga is deeply engaged in social welfare, which enhances his community standing. He organises free Vesak Dansals, distributes Poson festival stickers, and supports religious events like illuminating the Sumana Saman Devalaya (Figure 5). This community embeddedness fosters goodwill, a key asset for informal entrepreneurs (Seyfang & Smith, 2007). Employee Sajan noted: ‘Saranga is more than a boss, he cares about the community and supports us and the village. That makes working here special’.

Figure 5. Lighting of the Sumana Saman Devalaya in Ginigathena.

Source: Business’s Official Facebook Page – Ever Rich (2024).

Figure 6. Vesak Dansel.

Source: Business’s Official Facebook Page – Ever Rich (2024).

This blend of entrepreneurship and social responsibility strengthens Ever Rich’s legitimacy and contributes to sustained customer loyalty (Figure 6).

In the absence of formal advertising channels or corporate marketing budgets, Saranga leveraged social media platforms such as Facebook and TikTok to build his brand and connect with a wider audience. His online presence acts as a dynamic showcase of his work, highlighting customised interiors, lighting systems, sound installations and ongoing projects, which organically attract both local and regional customers.

Unlike traditional businesses, Saranga’s strategy focuses on visual storytelling and customer engagement, using video snippets, before-and-after shots and customer testimonials to build trust and social proof. This grassroots marketing approach resonates with research suggesting that digital platforms can amplify the reach of informal entrepreneurs and help them construct legitimacy in saturated or informal markets (Cooper et al., 2020; von Hippel, 2005).

One of his customers, Geethika, a fellow entrepreneur, remarked: ‘I first saw Saranga’s bus modification on TikTok. His design sense is clean, bold, and different. That’s when I contacted him, and since then I’ve always collaborated with him on vehicle projects’.

Through consistent social media use, Saranga has transformed digital platforms into affordable marketing tools, creating demand and expanding his reputation far beyond his physical locality. His case highlights how informal entrepreneurs integrate digital technologies with grassroots practices to scale their ventures and engage new markets (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Social Media Platforms.

Source: Business’s official social media platforms.

Conclusion

The story of Saranga Lakruwan and the rise of Ever Rich serves as a compelling case of how entrepreneurial bricolage and grassroots innovation can drive business creation and growth in resource-constrained environments. Through the lens of this qualitative case study, it becomes clear that Saranga’s success is not rooted in access to capital or advanced infrastructure, but in his capacity to improvise, recombine resources and innovate based on local needs, all core elements of the bricolage approach as outlined by Baker and Nelson (2005).

Themes such as ‘making do’ with available tools, bootstrapping and informal learning were foundational in explaining how Saranga initiated his enterprise from home with minimal input. His capacity to transform a basic ‘veel’ into a well-decorated, technically enhanced vehicle using only local materials reflects the essence of bricolage, creatively constructing value from ‘what is at hand’ (Baker & Nelson, 2005; Garud & Karnøe, 2003).

As the business matured, Saranga’s attention to customer-centred customisation and user-led innovation played a vital role in distinguishing his services. Modifications tailored to individual budgets and preferences, particularly for customers like Lasanthi, a bus fleet owner, and Nadith, a fellow entrepreneur, underscore how grassroots innovators like Saranga bridge market gaps left by formal industry players (Seyfang & Smith, 2007; von Hippel, 2005). His offerings, ranging from lighting systems to digital displays, demonstrate how user-driven feedback loops fuel iterative innovation and customer loyalty in informal economies.

Furthermore, the theme of market niche creation illustrates that Saranga successfully filled a void in the Ginigathena–Nawalapitiya region by offering vehicle interior modifications, an underserved service in the area. His ability to scale gradually, moving from home-based operations to a three-bus-capacity workshop with three employees, illustrates the power of incremental growth rooted in self-financing and demand responsiveness (Greve & Salaff, 2003).

Importantly, the study finds that entrepreneurial success in informal contexts is not solely economic. Saranga’s commitment to social value creation, through Vesak Dansals, Poson sticker giveaways, and religious contributions like illuminating the Sumana Saman Devalaya, exemplifies community-embedded entrepreneurship. These efforts generate reputational capital, enhance trust and consolidate his legitimacy as a local leader (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). Additionally, he uses social media platforms to market his services.

In sum, Saranga Lakruwan’s journey highlights how informal entrepreneurs, particularly in under-resourced rural settings, rely on personal resourcefulness, adaptive strategies and community engagement to achieve meaningful growth. His case affirms the relevance of bricolage theory in emerging economies and adds to the growing body of literature that sees informal, bottom-up innovation not as a survival tactic, but as a deliberate, strategic practice with transformative potential (Fisher, 2012; Seyfang & Smith, 2007).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Aldrich, H. E., & Zimmer, C. (1986). Entrepreneurship through social networks. In D. L. Sexton & R. W. Smilor (Eds), The art and science of entrepreneurship (pp. 3–23). Ballinger.

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.4

Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cooper, R., Samarasinghe, N., & Karunaratne, H. D. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing countries: Case of Sri Lanka. Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy, 9(2), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.7545/AJIP.2020.9.2.257

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Dhewantara, D., & Surya, I. B. K. (2021). Grassroots innovation: A review of innovation from below in Southeast Asia. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2020-0153

Ever Rich. (2024). Official Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100088985832810&mibextid=rS40aB7S9Ucbxw6v

Ever Rich. (2024). Official TikTok Page. https://www.tiktok.com/@ever.rich8?_r=1&_t=ZS-918mjy8OnBP

Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x

Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00100-2

Greve, A., & Salaff, J. W. (2003). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00029

Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental Politics, 16(4), 584–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010701419121

von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation. MIT Press.

Wickramasinghe, A., & Wimalaratana, W. (2016). Entrepreneurship development in Sri Lanka: The case of micro and small enterprises. Sri Lanka Journal of Economic Research, 4(2), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljer.v4i2.27

Wijesinghe, S., & Perera, K. (2020). National Innovation System in Sri Lanka: Gaps, opportunities and way forward [LIRNEasia working paper series]. https://lirneasia.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/NIS-Sri-Lanka-LIRNEasia-WP.pdf

World Bank. (2020). Sri Lanka jobs diagnostic: Building the foundation for more and better jobs. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/618571582602338591/sri-lanka-jobs-diagnostic

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications.