1Department of Management, Sikkim University (A Central University), Gangtok, Sikkim, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The goal of the study is to examine the interaction between green human resource management (HRM) and green creativity in India’s developing healthcare industry. Given that the healthcare industry is one that greatly contributes to waste generation and other environmental risks; thus, targeting this sector in inducing green creativity leads to a number of benefits to the country in terms of economy and ecology. Apart from this, governments’, policy makers’ and international agencies’ current attention on sustainability has justified the necessity of this work. This research work has been designed on a two-study approach, where both qualitative and quantitative approaches were used. Study 1 is qualitative in nature and uses content analysis to explore the sustainability emphasis of private and public hospitals. Study 2 is quantitative and involves empirical data collection from administrative and paramedics’ employees in various private hospitals of Delhi NCR. A self-administered questionnaire was used for collecting responses, and a total of 170 responses were analysed using IBM Amos 23.0. Details of the findings have been discussed in the article. The present research work is novel in an attempt at integrating two studies (mixed methodology) with mixed research designs in order to get a deeper understanding of embedded sustainability focus in healthcare organisations, especially in the context of an emerging economy. The study presents many implications for policymakers, professionals, government, sustainable activist and research scholars.

Green human resource management, green organisational citizenship, green value, green culture, content analysis, mixed research methodology

Introduction

5th June is celebrated worldwide as Environment Day. As per the United Nations Brundtland Commission (UNBC) (1987), sustainability is ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. The main aim of sustainability is to use methods and products which will not harm the environment by releasing any harmful by-products or deplete essential resources (Robinson & Adams, 2008). Reduced consumption of environmental assets and the use of alternative sources, including reducing waste and promoting reuse, can lead to positive changes (Dallas, 2008). But it is high time for us to take a pause and think, highlight, rethink and act, and understand what is at stake. Sustainability is crucial in today’s time. Various sectors, including manufacturing to service, are impacting ecology in their own way, and the healthcare sector is not an exception. In recent times, the healthcare sector has been facing immense pressure to calculate its policies with human well-being as well as environmental sustainability. Apart from this, the healthcare industry is one of the resource-intensive industries and is responsible for high-energy (electricity, fossil fuel and others) consumption, waste generation, carbon emission and other environmental degradations.

Hence, we understand that it is important to incorporate sustainable practices into hospitals, including their core and allied operations. All stakeholders have advocated for this at a global level, and as a result, green creativity has emerged for eco-innovation in all industries, including healthcare. Therefore, for sustainable development, every organisational function is accountable. The present study focuses on green human resource management (HRM), green culture, green organisational citizenship (GOCB) and green values in promoting green creativity at the workplace. As a matter of fact, more and more organisations understand the importance, impact and role of green HRM in the adoption of sustainability. While green HRM encompasses all the practices which make the organisation focus on the environment and its related concerns. Ultimately, the green HRM practices lead to the formulation of eco-friendly or environment-friendly practices among employees at the workplace.

This article is structured into several segments and sub-segments. The article is divided into two parts; the first segment deals with introduction followed by the second, which includes literature review and hypothesis development. This is followed by methodology, data analysis, and discussion with implications, future directions and conclusions.

At present, we do not get to choose between sustainability and innovation, especially in the healthcare sector, which consumes vast amounts of energy along with maximum waste generation. It is understood that healthcare works for human well-being, leading to the production of large quantities of waste and pollution. And due to this contrast, there is a pressing need for sustainable practices in the healthcare industry, nationally as well as internationally. Hence, all organisational functions need to come forward as enablers of environmental sustainability at the workplace. However, we still have limited studies and research in this domain providing answers.

This study is bridging the knowledge gap by throwing light on the private healthcare sector of India. Delhi, being the capital of India and a metropolitan city, has the top-quality healthcare facilities and services. We chose this region as it provides a large and diversified sample for our study. In addition to this, previous studies have lacked a qualitative and comparative aspect, which is the novelty and value of the present study. Furthermore, this study fills the methodological gap by using a mixed approach (qualitative and quantitative design) within the healthcare domain.

Based on the above discussion, the present study has tried to answer the following research questions:

Rationale of the Study

Hospitals, being the centres of healing and well-being, are amongst the biggest contributors of environmental deterioration, generating large amounts of both medical, biomedical and non-medical waste. Hence, all over the globe, sustainability in healthcare has become an important focus. The healthcare sector has a crucial impact on environmental degradation and therefore owes the responsibility to adopt preventive measures to minimise the negative impacts of the waste generated. Hospitals have various departments ranging from patient care to residential facilities, including laundry, kitchen and parking lots, contributing to the environmental footprint. When sustainable practices are implemented, hospitals will have the potential to lead by example in addressing waste generation and environmental challenges. While several hospitals have adopted and implemented green practices around the world to create a greener planet, we hope this momentum will gain speed gradually. As of today, there is an increase in the number of hospitals embracing sustainability and inspiring other industries to rethink and redesign their own green practices. Although there has been extensive research on topics pertaining to green HRM in industries from manufacturing to service, the healthcare sector remains underexplored. This study aims to focus on the private hospitals and their strategies of green HRM.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Green HRM is significant in promoting sustainability at the workplace through HR strategies (Mandip, 2012). Implementation of green HRM will increase the likelihood of organisational environmental sustainability success. These green HRM practices are defined as HR strategies, which improve pro-environmental behaviour (Kramar, 2014). Thus, HR policies, which help the organisation in achieving goals and protecting the environment from the adverse effects caused by the operations of the organisation, can be called green HRM. Organisations incorporate green HRM practices to strengthen environmental goals and encourage employees to contribute in achieving that goal through appropriate strategies (Jackson et al., 2011). Resultant, green HRM enables the strategic ground for a long-term view of human capital investment by promoting desirable behaviours, recognising employees’ contributions and ensuring employees’ career development path (Robertson & Barling, 2017). Additionally, organisations endeavour to maximise return on investment (ROI) in their members by actively integrating employee input into organisational outcomes (Jabbour et al., 2015).

There are various ways by which green human resource practices induce green behaviour among employees, such as green culture, green values and green organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). A number of studies (Harris & Crane, 2002; Holt & Anthony, 2000; Kramar, 2014; Mandip, 2012) have confirmed a significant relationship among all these through various mediation and moderation approaches. Through their attitudes, values, beliefs and activities, members of green culture organisations demonstrate a care for the environment (Roscoe et al., 2019). Here, values mean ‘what internal customers (employees) consider moral and ethical for the ecology’ (Harris & Crane, 2002; Holt & Anthony, 2000). Studies by Valsiner (2014), Ratner (2017) and Gl.png) veanu and Wagoner (2015) state that culture involves active and selective internalisation of messages by an individual who produces and expresses meaning, which then creates differences between personal and collective culture. While belief reflects the perception of employees towards what counts as right or wrong and as acceptable or unacceptable concerning the environment and its safety (Roscoe et al., 2019). It also influences the actions towards environmental protection (Chang, 2015).

veanu and Wagoner (2015) state that culture involves active and selective internalisation of messages by an individual who produces and expresses meaning, which then creates differences between personal and collective culture. While belief reflects the perception of employees towards what counts as right or wrong and as acceptable or unacceptable concerning the environment and its safety (Roscoe et al., 2019). It also influences the actions towards environmental protection (Chang, 2015).

Previous studies have found a significant association between green HRM and green culture (Al-Alawneh et al., 2024; Amini et al., 2024; Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002), depicting that green HRM practices in turn generate a higher degree of green culture in an organisation (Pellegrini et al., 2018). Since it is crucial for coordinating company ideology with employee beliefs and actions, the human resource department serves as the cornerstone in this (Roscoe et al., 2019). Thus, the following hypothesis has been suggested:

H1: Green HRM significantly impacts the green culture in organisation.

In addition to having a stronger impact on social and psychological influence than on environmental performance, green culture is associated with organisational citizenship behaviour (Temminck et al., 2015). Further, this also confirmed a positive correlation, and the stronger the green culture, the higher the GOCB (Dumont et al., 2017). Consequently, we see green culture advancing GOCB. Similarly, the human resource department encourages employees and supports pro-environmental efforts (Amini et al., 2024). Hence, green HRM practices foster commitment towards pro-environmental behaviour (Pellegrini et al., 2018).

As mentioned previously, continuous participation and involvement in green initiatives at the workplace by employees will encourage and boost pro-environmental behaviour. In summary, employees will reinforce GOCB when such practices align with their own values. Furthermore, fostering GOCB starts with assisting employees in truly seeing their value. Studies (Daily & Huang, 2001; Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, 2011) stated that there is a rise in GOCB when employees of the organisations take part actively in environmental initiatives. Additionally, employee empowerment is key to ensuring a workplace culture of continuous improvement while reducing bureaucracy and bypassing red-tapism (Roscoe et al., 2019).

H2: Green culture significantly influences GOCB.

As per Organ (1988), OCB can be understood as voluntary actions, which employees perform at the workplace and which go beyond their job descriptions and are not officially awarded, but play a crucial role in supporting how organisations function. On the other hand, green creativity involves the creation of new and innovative green services, products and practices, which are original and add real value (Amabile, 1988). Liu et al. (2019) found that OCB is positively related to green creativity. They conducted a study on a sample of Chinese employees and found that those who engaged in OCB also generated more green creative and innovative ideas than those who did not. Further, OCB provides employees with a sense of ownership and belonging in their workplace, which in turn motivates them to generate creative and new ideas for sustainability.

Similarly, Hsiao and Wang (2020) found that OCB is positively related to green creativity in the hospitality industry in Taiwan. When employees engage in OCB, they experience a sense of intrinsic motivation, which enhances their creativity for sustainability (Hsiao & Wang, 2020). Furthermore, Liu et al. (2020) also opined that OCB is positively related to green creativity. As per them, when employees engage in OCB, they become more committed to their organisation’s goals and values, which motivates them to generate creative ideas for sustainability.

In addition, Wu et al. (2021) investigated the relationship in the context of Chinese universities and found that OCB is positively related to green creativity. OCB gives them a sense of responsibility and accountability towards the environment, which motivates them to generate creative ideas for sustainability. Overall, the literature indicates a positive relationship between OCB and green creativity. This relationship is likely to be influenced by factors such as organisational culture, job satisfaction and employee motivation. Keeping this discussion as pivotal, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:Green organisational citizenship behaviour is positively associated with green creativity.

Green values can be understood as the significance of individual or group values in protecting the environment (Mustonen et al., 2016). Hence, these can be called a set of guiding principles, which shape individual attitudes, decisions and behaviours. These values extend beyond awareness, influencing lifestyle choices and ethical considerations. Green values serve as the foundation of sustainability goals and corporate social responsibility, linking personal beliefs and organisational commitment to environmental well-being. Additionally, Li et al. (2020) and Wu et al. (2021) stated that commitment towards the environment increases motivation, which in turn increases creativity and green output.

Over time, various studies (Andersson et al., 2005; Chou, 2014; Kim & Seock, 2019; Schultz et al., 2005) have suggested a direct relationship between green behaviour and green values, but we are yet to understand the moderating or mediating role of green values. Dumont et al. (2017) showed that the organisation which promotes green values will have green culture, which in turn leads to a higher level of GOCB and creativity. Strong green values are interrelated with exhibiting green behaviour addressing environmental challenges (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021). Green values will shape and decide how employees will respond towards sustainability stimuli of organisations. If employees have strong green values, that will translate into their actual behaviour at the workplace. Hence, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

H4:Green values moderate the relationship between GOCB and green creativity.

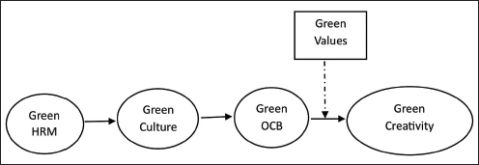

Thus, based on the above discussion, the following research model has been proposed.

Method

The present study has adopted the mixed research approach to answer the underlying research questions. Two studies have been conducted for the present research work. Both qualitative as well as quantitative designs were used. For the qualitative research approach, we have used content analysis of official websites, whereas the quantitative research study used a descriptive research design.

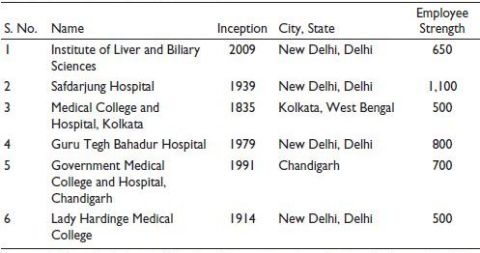

Study 1: First, a qualitative research design has been used to study disclosure practices of the healthcare industry, where both public and private hospitals were selected for comparative purposes. For this study, we have used the SCImago ranking (2023) for Indian hospitals based on research focus. We have identified five private and five public hospitals from the list for our study. There are different types of hospitals that serve the multifaceted needs of society. Therefore, we divided the hospitals into two parts based on the classification between public and private sectors. A total of 10 hospitals were selected for content analysis of environmental disclosure on their official websites. Table 1 and Table 2 contain the list of public and private sector hospitals in the SCImago (2023) ranking.

Table 1. SCImago Ranking (Public Sector).

Source: SCImago Institutions Ranking. https://www.scimagoir.com/rankings.php?sector=Health&country=IND

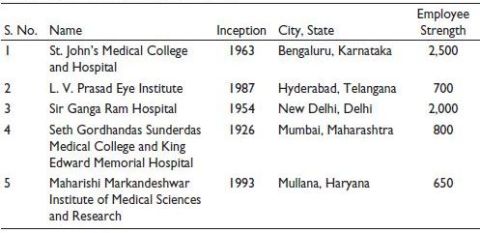

Table 2. SCImago Ranking (Private Sector).

Source: SCImago Institutions Ranking.

Table 2 presents the list of private sector hospitals taken from the SCImago ranking (2023).

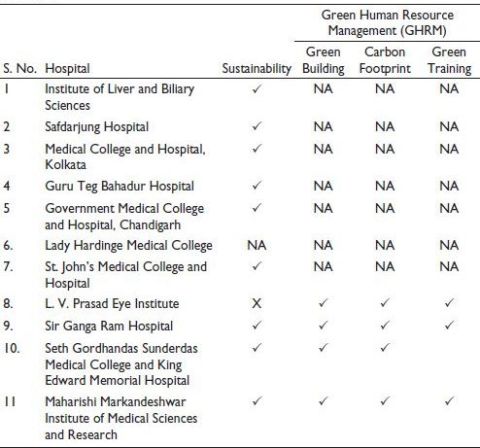

After the selection of hospitals, their respective websites have been explored for disclosure of sustainability practices and initiatives. It has been assumed that organisations with ecological focus and consideration tend to disclose and emphasise more on sustainability practices on their official websites and other important disclosure documents. Therefore, the website of each selected hospital has been thoroughly explored for sustainability-related disclosures, more specifically, green HRM (green building, green training and any other). Thereafter, content analysis has been performed on the environmental disclosure of every hospital.

Study 2: After qualitative analysis, Study 2 has been conducted using a quantitative research approach. In order to find out the influence of green HRM practices on green creativity of employees, a descriptive research design has been used because of its appropriateness in hypothesis testing.

Sample and Sampling Strategy

The study includes HR, administrative staff and paramedical staff of private hospitals in Delhi NCR. Employees who were on direct payrolls were included in the study, assuming their direct involvement in and relevance to the core functions of hospitals. Purposive sampling technique (non-probability sampling strategy) has been used in order to obtain the required respondents.

Data Collection Procedure

Primary data were collected using a structured questionnaire, prepared from extensive literature review (details of which are given in the following subsection). A total of 200 print questionnaires were distributed to HR, administrative staff and paramedical staff of private hospitals only. Out of these, 20 responses were incomplete and 10 were not returned. Thus, the final sample size consisted of 170 responses. Thus, this sample size is considered appropriate for many research purposes and can yield statistically robust results.

Questionnaire and Measures

The questionnaires contained questions related to green HRM practices, green values and green creativity, allowing participants to provide numerical or categorical responses. There were two sections in the questionnaire. To begin with, the first section consisted of demographic questions to answer, followed by questions on constructs for the study, including green HRM (Saeed et al., 2019), green culture (Marshall et al., 2015; Umrani et al., 2022), GOCB (Hooi et al., 2022; Pham et al., 2018), green value (Hooi et al., 2022) and green creativity (Barczak et al., 2010; Rego et al., 2007). Detailed items of each construct/scale can be seen in Annexure A in the supplementary material.

Analysis and Findings

Study 1

The findings of this study reveal that private hospitals in India employ various green HRM practices, including comprehensive training programmes, rewards and recognition, and career development opportunities. These practices are designed to attract and retain skilled healthcare professionals, enhance employee satisfaction and improve organisational performance. These private hospitals struggle with constraints of limited budget and funding, which puts them in a dilemma. However, on the other hand, public hospitals also deal with restricted budgets and bureaucratic interventions that affect the effectiveness and morale of employees. Hospitals from both sectors share similar priorities; however, their approaches differ. Despite the differences, both hospitals value the need for robust green HRM practices.

Table 3 presents the comparative content analysis of public and private hospitals in terms of their sustainability disclosure.

Study 2

Structure equation modelling has been done using Amos 23.0.

Measurement Model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA):

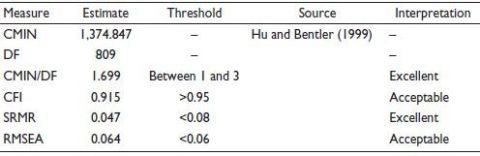

To ascertain if the measurement model fitted, Amos 26.0.0 trial version was used to perform CFA with maximum likelihood estimation. A component of CFA was evaluating the factor loadings for every item. All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < .05) and ranged from 0.71 to 0.886, demonstrating robust relationships between the observed variables and their respective latent constructs (see Annexure B in the supplementary material). The overall goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using the model fit measures, and all values that fell below the common acceptability criterion agreed with the threshold values proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999). A satisfactory fit was obtained with the five-component model (green HRM, green value, GOCB, green culture, green creativity) (see Table 4).

Table 3. Comparative Content Analysis of Public and Private Hospitals in Sustainability Disclosure.

Table 4. Model Fit Measures.

Note: CFI: Comparative fit index; CMIN: Chi-square minimum discrepancy; DF: Degrees of freedom; RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation; SRMR: Standardised root mean square residual.

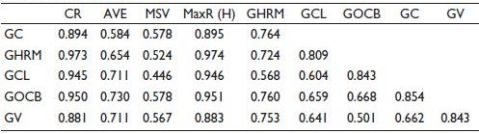

Table 5. Reliability and Validity.

Source: Gaskin and James (2019), ‘Master Validity Tool’, Amos Plugin. Gaskination’s StatWiki.

Within a CFA framework, the study rigorously evaluated construct validity and reliability. Convergent validity on the grounds of average variance extracted (AVE), all latent constructs again passed the conventional cut-off level of 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) as evidence (by the bold values of Table 5) that the model was operating adequately. Discriminant validity was established by comparing the square root of AVE values (diagonals in Table 5) with inter-construct correlations (below the diagonals), in which the diagonal value of each construct was larger than its correlations with other constructs, demonstrating the discriminant of each construct from the other constructs.

According to Hair et al. (2010), reliability, also known as internal consistency, is another convergent validity metric. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is a commonly used metric for assessing internal consistency. However, as composite reliability (CR) is regarded as a better option than alpha coefficient, it is typically utilised in comparison with Cronbach’s alpha (Chin, 2009; Kumar & Saha, 2017). A construct’s CR value needs to be more than 0.7 in order for it to be deemed dependable and internally consistent (Hair et al., 2010; Nunnally, 1978). All latent constructs had CR values significantly higher than the cut-off value of 0.7, indicating the reliability of the constructs (refer to Table 5).

Structural Model.

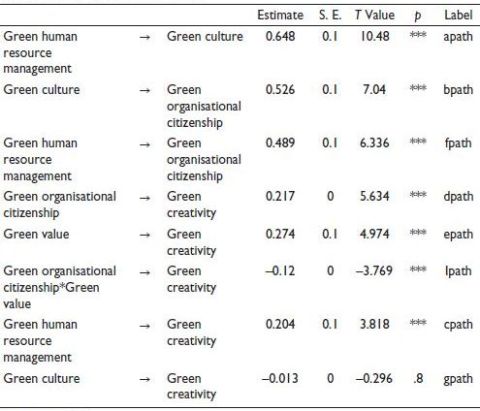

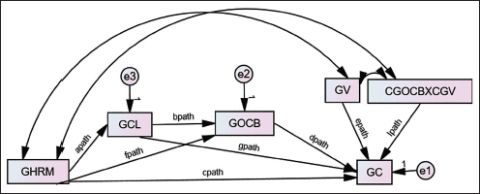

After the measurement model, the structural model was tested by using 5,000 bootstraps at 95% level of confidence. To scrutinise the association between green HRM and green creativity, the factor scores from the CFA of the measurement model were imputed using AMOS path analysis. As a measure of the hypothesis, green culture and GOCB were tested as mediators and green value as a moderator (see Figure 1). Table 6 provides a thorough breakdown of the regression analysis’s findings, including parameter estimates, the crucial ratio (T value) and the associated p values (Please see Figure 2 for path).

Green HRM is positively related to green culture (estimate = 0.648, p < .05) and GOCB (estimate = 0.489, p < .05). Green HRM is positively related to green creativity also (estimate = 0.204, p < .05). Green culture is positively related to GOCB (estimate = 0.526, p < .05) but not related to green creativity (estimate = –0.013, p > .05). Therefore, green culture encourages the green organisational citizenship behaviour but does not impact the green creativity. GOCB has a significant impact on green creativity (estimate = 0.217, p < .05). Therefore, we can conclude that green culture somewhere does not directly influence green creativity but indirectly impacts it, which will be further tested in mediation analysis. The interaction of green value and GOCB has a significant impact on green creativity (estimate = –0.12, p < .05). It means green value was moderating the relationship.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework.

Note: HRM: Human resource management; OCB: Organisational citizenship.

Table 6. Structural Model Estimates.

Note: ***p < .001.

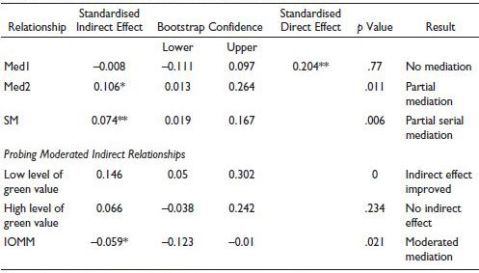

Table 7. Mediation and Moderation Analysis (Bootstrapping).

Notes: **p < .001; *p < .05. IOMM: Index of moderated mediation.

Mediation and Moderation Analysis

Despite being extremely well-liked and frequently applied, the method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) has faced criticism in recent times (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) for two primary reasons: inconsistent mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2007) and relatively low statistical power (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). When the path coefficient between the predictor and the mediator (a) is negative, resulting to a negative indirect effect (ab), and the total effect is very small and non-significant (even though both direct and indirect effects are individually substantial), inconsistent mediation—though extremely rare—occurs. Owing to the shortcomings of Baron and Kenny’s (1986) methodology, the present study, the bootstrapping approach by Preacher and Hayes (2008) was used with 5,000 sub-samples and a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval to estimate the indirect effect in addition to the direct path, as described in the research model. The direct, indirect and total effects—the outcomes of the mediation and moderation analysis—are described in Table 7 and Figure 2. For analysing the effects, the following paths were studied:

Med1=apath*gpath (Mediation of green culture from GreenHRM to green creativity)

Med2=fpath*dpath (Mediation of GOCB from GreenrHRM to green creativity)

SM=apath*bpath*dpath (Serial Mediation of green culture and GOCB from GeenHRM to green creativity)

OneSDbelow=fpath*((Ipath*–0.69021)+dpath)

OneSDabove=fpath*((Ipath*0.69021)+dpath)

IOMM=fpath*Ipath (Interaction of moderated mediation)

Figure 2. Structural Model.

The indirect effect of green HRM on green creativity through green culture was found not significant (estimate = –0.008, p = .77). Hence, we see that green culture is not mediating the relation between green HRM and green creativity. However, the indirect effect of green HRM on green creativity via GOCB is found to be significant (estimate = 0.106*, p < .05) including the direct relationship with GOCB as well. Hence, we understand GOCB is not fully but partially mediating between green HRM and GOCB.

The results of the indirect effect of both interceding to green creativity are found to be significant (estimate = 0.074, p < .05). Hence, we can say that serial mediation occurs. As per the model, we see green HRM and green creativity are mediated by two variables, green culture and GOCB. Additionally, there is a direct effect of green HRM to green creativity in the presence of green culture and GOCB which are also significant (estimate = 0.204, p < .05). Therefore, we can see it as a case of partial serial mediation as green culture and GOCB partially mediate the relation between green HRM and green creativity.

Results show that when the green value is low, the indirect effect was 0.146 and significant (p < .05). But at a higher level of green value, the indirect effect was 0.066 and p = .234, which means the relationship became not significant. Now it is required to assess whether the indirect effect was being moderated. As per the index of moderated mediation (IOMM) by Baron and Kenny (1986), to determine whether moderated mediation was occurring, the analysis looks at whether the slope is substantially different from zero. It is –0.059 with p value .021; therefore, green value was moderating the indirect effect from green HRM to green creativity through GOCB. The strength of this indirect effect changes with green value.

Discussion

In the present work, Study 1 aimed to compare the sustainability focus of both private and public healthcare organisations. It is seen that private hospitals have a greater focus on sustainability and their practices compared to public hospitals. The public health sector is largely influenced by complex determinants, namely occupational conditions and corporate practices. These determinants indirectly influence system inequalities and organisational behaviour (Park et al., 2025). Their websites contain more mentions and disclosures on sustainability practices like green HRM, green building and carbon emissions compared to their counterpart public sector organisations. Private hospitals tend to show more concern towards ecological issues and challenges, possibly due to goodwill, company image, regulatory compliance and competition. Thus, the findings of this study were further extended in Study 2, where employees of private hospitals were included in the sampling for understanding different facets of sustainability in organisational imperatives. Thus, Study 2 aimed to investigate the relationship between green HRM and green creativity in private healthcare setups in Delhi NCR. The above research has included green HRM, which emerged for the first time in 2018 (Renwick et al., 2008). Moreover, our study is an extension to the existing study of green HRM but with a moderating green value on green creativity. Green HRM practices play a critical and most important role in shaping the organisational culture. They do the above by embedding sustainability into the core values and daily operations. Hence, we can say green HRM practices are of utmost importance in making crucial sustainability changes (Yong et al., 2020). The results of our research support our notion that when green HRM is strong, it leads to a stronger green culture (Hooi et al., 2021). Our results are compatible with the findings of many previous studies (Ahmed et al., 2021; Yong et al., 2020), which demonstrated that green culture is an important antecedent for environmental performance. These hospitals have their sustainability reports published on their websites, which state that sustainability reporting offers additional benefits and is embedded in organisations’ strategic priorities (Higgins & Coffey, 2016). In strategic parlance, companies use this sustainability reporting as a strategic imperative that is embedded in their important decision-making processes. Thus, apart from the sustainability focus, reporting also offers additional benefits to the companies (hospitals, in this case).

The study also resulted in green HRM practices often leading to the encouragement of employees to go beyond their formal roles. Further, a strong green culture creates social norms, which encourage GOCB. When environmental sustainability becomes a part of organisational identity, employees feel a sense of moral obligation in engaging and demonstrating GOCB. This study verifies the direct effect of green HRM on green creativity. In addition, it also highlights how the implementation of green HRM practices can increase environmental sustainability (Yusoff et al., 2020). However, in a contrary study conducted by Hooi et al. (2022), our finding depicts that as green value increases, the moderating effect weakens, and the relationship becomes insignificant.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the present research, all efforts have been made to minimise the limitations and increase the robustness of the findings. However, it is important to discuss the significant ones. In Study 1, the only official websites were used for content analysis whereas other disclosure documents, such as annual reports, could offer deeper insights into the sustainability focus of the respective organisations. Second, only SCImago ranking (2023) was used for sampling, whereas other domestic rankings can also be used to select varied hospitals. Additionally, hospitals from other regions could also be used to compare the findings of content analysis for different contextual settings. In Study 2, different industries, cultural context and organisational settings may yield varying results. We could proceed ahead with the analysis of green HRM at all levels of the organisation, which represents a limitation of this study. Further, there could be other variables of green HRM added to the study along with cross-industry and cross-country comparative studies. Additionally, studies could be extended further in longitudinal designs to measure the impacts of variables over time.

Implications and Conclusion

The findings of the study have implications for organisations aiming to foster sustainability and green creativity. Hospitals can leverage green HRM practices to develop a culture of environmental accountability and responsiveness, which can enhance employees’ creative contributions to sustainable initiatives. HR departments can play a pivotal role in implementing and promoting green HRM practices that align with the company’s sustainability goals. The study suggests the importance of training programmes that focus on promoting green values among employees. Hospitals can invest in training initiatives that emphasise the significance of environmental responsibility and its alignment with creativity. Hospitals should consider including sustainability-related performance metrics in their employee appraisal systems. Recognising and rewarding the employees for their contributions to sustainability and green creativity can motivate further engagement. HR departments should integrate sustainability criteria into recruitment and selection policies. This integration will ensure that selected candidates and employees not only possess the necessary capabilities and skills but also have alignment with the organisation’s green values and their jobs.

In conclusion, the study sheds light on the intricate relationship between green HRM practices, green values and green creativity within private hospitals. It underscores the pivotal role of HR departments in fostering a culture of sustainability, where employees are not only encouraged to adopt green values but also exhibit enhanced creative problem-solving abilities related to environmental challenges. The findings emphasise that green HRM practices are more than just a compliance requirement; they serve as catalysts for green creativity. By investing in green HRM initiatives, organisations can inspire employees to generate innovative and creative solutions that contribute to sustainable development. As we move forward, it is essential for both scholars and practitioners to delve deeper into this realm. Future research should explore the nuances of how different green HRM strategies impact various aspects of green creativity and sustainability across diverse organisational contexts. In doing so, we can advance our understanding of how HRM practices can serve as powerful tools in the pursuit of a more environmentally responsible and creative workforce. Ultimately, the integration of green values into HRM can be a driving force for sustainable innovation in the workplace and beyond.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the contribution made by the anonymous participants of the study.

Authors’ Contributions

Shalini Shukla has contributed to idea generation, conceptual framework, questionnaire development and structuring and writing of the article. Hera Fatima Iqbal has contributed to data collection, interpretation and writing section. Ila Pandey did data analysis.

Consent to Participate

Each participant has provided informed consent. They were informed orally as well as in writing about volunteer participation. Respondents were assured of the academic nature of the study and anonymity of their responses.

Data Availability

Data can be made available on reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Shalini Shukla  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4369-3527

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4369-3527

Hera Fatima Iqbal  https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5387-9434

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5387-9434

Ila Pandey  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7713-3811

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7713-3811

Ahmed, U., Umrani, W. A., Yousaf, A., Siddiqui, M. A., & Pahi, M. H. (2021). Developing faithful stewardship for environment through green HRM. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3115–3133.

Al-Alawneh, R., Othman, M., & Zaid, A. A. (2024). Green HRM impact on environmental performance in higher education with mediating roles of management support and green culture. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(6), 1141–1164.

Al-Ghazali, B. M., & Afsar, B. (2021). Retracted: Green human resource management and employees’ green creativity: The roles of green behavioral intention and individual green values. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 536–536.

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 123–167.

Amini, M. Y., Tang, Z., & Besharat, A. (2024). Greening university practices: Empowering eco-conscious behavior, transforming sustainable culture, and shaping greener institutional awareness through strategic green HRM initiatives. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 13(1), 232–251.

Andersson, L., Shivarajan, S., & Blau, G. (2005). Enacting ecological sustainability in the MNC: A test of an adapted value-belief-norm framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(3), 295–305.

Barczak, G., Lassk, F., & Mulki, J. (2010). Antecedents of team creativity: An examination of team emotional intelligence, team trust and collaborative culture. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(4), 332–345.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Chang, C. H. (2015). Proactive and reactive corporate social responsibility: Antecedent and consequence. Management Decision, 53(2), 451–468.

Chin, W. W. (2009). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 655–690). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Chou, C. J. (2014). Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism Management, 40, 436–446.

Daily, B. F., & Huang, S. C. (2001). Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 21(12), 1539–1552.

Dallas, N. (2008). Green business basics: 24 lessons for meeting the challenges of global warming. McGraw Hill.

Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2017). Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627.

Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239.

Gaskin, J., & James, M. (2019). HTMT plugin for AMOS.

Gl.png) veanu, V., & Wagoner, B. (2015). Culture & psychology: The first two decades and beyond. Culture & Psychology, 21(4), 429–438.

veanu, V., & Wagoner, B. (2015). Culture & psychology: The first two decades and beyond. Culture & Psychology, 21(4), 429–438.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Harris, L. C., & Crane, A. (2002). The greening of organizational culture: Management views on the depth, degree and diffusion of change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 15(3), 214–234.

Higgins, C., & Coffey, B. (2016). Improving how sustainability reports drive change: A critical discourse analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 136, 18–29.

Holt, D., & Anthony, S. (2000). Exploring ‘green’ culture in Nortel and Middlesex University. Eco-Management and Auditing: The Journal of Corporate Environmental Management, 7(3), 143–154.

Hooi, L. W., Liu, M. S., & Lin, J. J. (2022). Green human resource management and green organizational citizenship behavior: Do green culture and green values matter? International Journal of Manpower, 43(3), 763–785.

Hsiao, C. H., & Wang, F. J. (2020). Proactive personality and job performance of athletic coaches: Organizational citizenship behavior as mediator. Palgrave Communications, 6(1), 1–8.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Jabbour, C. J. C., Jugend, D., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., Gunasekaran, A., & Latan, H. (2015). Green product development and performance of Brazilian firms: Measuring the role of human and technical aspects. Journal of Cleaner Production, 87, 442–451.

Jackson, S. E., Renwick, D. W., Jabbour, C. J., & Muller-Camen, M. (2011). State-of-the-art and future directions for green human resource management: Introduction to the special issue. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(2), 99–116.

Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, C. (2011). How green are HRM practices, organizational culture, learning and teamwork? A Brazilian study. Industrial and Commercial Training, 43(2), 98–105.

Kim, S. H., & Seock, Y. K. (2019). The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 83–90.

Kramar, R. (2014). Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8), 1069–1089.

Kumar, S. P., & Saha, S. (2017). Influence of trust and participation in decision making on employee attitudes in Indian public sector undertakings. Sage Open, 7(3), 2158244017733030.

Li, W., Bhutto, T. A., Xuhui, W., Maitlo, Q., Ullah Zafar, A., & Bhutto, N. A. (2020). Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 255, 120229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120229

Liu, J., Wang, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2020). Climate for innovation and employee creativity: An information processing perspective. International Journal of Manpower, 41(4), 341–356.

Liu, W., Zhou, Z. E., & Che, X. X. (2019). Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(5), 657–669.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614.

Mandip, G. (2012). Green HRM: People management commitment to environmental sustainability. Research Journal of Recent Sciences, 2277(1), 2502.

Marshall, D., McCarthy, L., McGrath, P., & Claudy, M. (2015). Going above and beyond: How sustainability culture and entrepreneurial orientation drive social sustainability supply chain practice adoption. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 20(4), 434–454.

Mustonen, N., Karjaluoto, H., & Jayawardhena, C. (2016). Customer environmental values and their contribution to loyalty in industrial markets. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(7), 512–528.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer.

Organ, D. W. (1988). A restatement of the satisfaction-performance hypothesis. Journal of Management, 14(4), 547–557.

Park, J., Brown, J. A., & Husted, B. W. (2025). Health is everyone’s business: Integrating business and public health for lasting impact. Business & Society, 64(3), 423–440.

Pellegrini, C., Rizzi, F., & Frey, M. (2018). The role of sustainable human resource practices in influencing employee behavior for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1221–1232.

Pham, T. N., Phan, Q. P. T., Tu?ková, Z., Vo, T. N., & Nguyen, L. H. (2018). Enhancing the organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of green training and organizational culture. Management & Marketing-Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 13(4), 1174–1189.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Ratner, C. (2017). The discrepancy between macro culture and individual, lived psychology: An ethnographic example of Chinese moral behavior. Culture & Psychology, 23(3), 356–371.

Rego, A., Sousa, F., Pina e Cunha, M., Correia, A., & Saur-Amaral, I. (2007). Leader self-reported emotional intelligence and perceived employee creativity: An exploratory study. Creativity and Innovation Management, 16(3), 250–264.

Renwick, D., Redman, T., & Maguire, S. (2008). Green HRM: A review, process model, and research agenda. University of Sheffield Management School Discussion Paper, 1(1), 1–46.

Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2017). Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Research, 75, 57–66.

Robinson, C., & Adams, N. (2008). Unlocking the potential: The role of universities in pursuing regeneration and promoting sustainable communities. Local Economy, 23(4), 277–289.

Roscoe, S., Subramanian, N., Jabbour, C. J., & Chong, T. (2019). Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 737–749.

Saeed, B. B., Afsar, B., Hafeez, S., Khan, I., Tahir, M., & Afridi, M. A. (2019). Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 424–438.

Schultz, P. W., Gouveia, V. V., Cameron, L. D., Tankha, G., Schmuck, P., & Fran?k, M. (2005). Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 457–475.

Temminck, E., Mearns, K., & Fruhen, L. (2015). Motivating employees towards sustainable behaviour. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(6), 402–412.

Umrani, W. A., Channa, N. A., Ahmed, U., Syed, J., Pahi, M. H., & Ramayah, T. (2022). The laws of attraction: Role of green human resources, culture and environmental performance in the hospitality sector. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103, 103222.

Valsiner, J. (2014). Functional reality of the quasi-real: Gegenstandstheorie and cultural psychology today. Culture & Psychology, 20(3), 285–307.

Wu, J., Chen, D., Bian, Z., Shen, T., Zhang, W., & Cai, W. (2021). How does green training boost employee green creativity? A sequential mediation process model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759548

Yong, J. Y., Yusliza, M. Y., Ramayah, T., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Sehnem, S., & Mani, V. (2020). Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(1), 212–228.

Yu, J., & Cooper, H. (1983). A quantitative review of research design effects on response rates to questionnaires. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(1), 36–44.

Yusoff, Y. M., Nejati, M., Kee, D. M. H., & Amran, A. (2020). Linking green human resource management practices to environmental performance in hotel industry. Global Business Review, 21(3), 663–680.