1Faculty of Postgraduate Studies and Professional Advancement, NSBM Green University, Homagama, Sri Lanka

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This study explores the impact of sustainability practices on brand value in Sri Lanka’s fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector, emphasising the mediating role of consumer perception. In recent years, sustainability has become an integral part of corporate strategy, with environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices increasingly shaping consumer expectations and business performance. However, limited empirical evidence exists on how these practices translate into consumer-driven brand value within emerging markets such as Sri Lanka. Addressing this gap, the study integrates stakeholder theory, the resource-based view and brand equity theory to examine how ESG practices influence consumer perception and subsequently, brand value. Adopting a quantitative, cross-sectional research design, data were collected through an online structured survey from 418 Sri Lankan consumers who had recently interacted with leading FMCG brands like Nestlé, Keells, Dilmah, Kotmale and Elephant House. Using partial least squares structural equation modelling via SmartPLS, the analysis confirmed that all three dimensions of sustainability (ESG) have significant positive effects on consumer perception. Moreover, consumer perception exhibited a strong, positive influence on brand value and served as a significant partial mediator between sustainability practices and brand value. The findings affirm that sustainability initiatives not only enhance corporate reputation but also serve as strategic assets that strengthen consumer-based brand equity in competitive markets. The study contributes to the growing body of research linking ESG integration to brand performance in emerging economies and provides actionable insights for managers seeking to enhance brand value through authentic, transparent and socially responsible practices.

Sustainability, environmental, social and governance, consumer perception, brand value, fast-moving consumer goods

Introduction

The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry is one of Sri Lanka’s most dynamic and economically significant sectors, shaping daily consumption patterns and contributing notably to national development. Covering essential products such as food, beverages and personal care items, the sector supports both household well-being and macroeconomic growth. With rising global emphasis on sustainability, FMCG firms are increasingly adopting environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices that reflect responsible and long-term business conduct (Kumar & Christodoulopoulou, 2014).

In Sri Lanka, the FMCG sector accounts for about 14% of GDP and employs over 15% of the workforce (Sunday Times, 2024). As globalisation and consumer awareness continue to grow, firms face increasing pressure to integrate sustainability into their strategic frameworks. Sustainability initiatives now extend beyond compliance to influence brand identity, trust and competitiveness. Leading brands such as Nestlé Lanka, Elephant House, Kotmale, Dilmah and Keells have implemented initiatives in renewable energy, ethical sourcing, waste reduction and community development. These companies also rank among Sri Lanka’s 100 most valuable brands (Brand Finance Plc, 2023), reflecting both market prominence and active engagement in sustainability communication.

For instance, Nestlé Lanka has adopted recyclable packaging and renewable energy systems, Elephant House focuses on energy-efficient production, Kotmale promotes ethical dairy sourcing, Dilmah is noted for biodiversity conservation, and Keells has introduced eco-friendly retail operations. Such initiatives aim not only to reduce environmental impact but also to enhance brand reputation through responsible business practices. This diversity provides a suitable basis to explore how ESG practices affect consumer perception and brand value in a developing market context.

Although extensive research in developed countries has shown that sustainability positively influences trust, loyalty and brand equity (Noh & Johnson, 2019; Saeidi et al., 2015), empirical evidence from developing economies like Sri Lanka remains limited. Local consumers are increasingly aware of global sustainability trends, yet their interpretations and responses may differ from those in Western contexts. Hence, it is unclear whether Sri Lankan consumers recognise and reward a firm’s sustainability efforts in ways that enhance brand value.

Another gap concerns the mediating role of consumer perception. While theories such as stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), the resource-based view (Barney, 1991) and brand equity theory (Aaker, 1991) highlight the value of intangible resources like reputation, few studies in South Asia have tested whether consumer perception connects sustainability initiatives with brand equity. Understanding this mediation is vital, as consumer perception determines how corporate actions are interpreted and valued.

This study, therefore, examines the impact of sustainability practices on brand value in Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector, considering consumer perception as a mediating variable. Using survey data from 418 respondents and partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), the study evaluates the relationships among ESG practices, consumer perception and brand value.

The research addresses four key questions:

The study fills two key gaps: the lack of empirical evidence on sustainability–brand relationships in developing economies and the limited exploration of consumer perception as a mediating factor. Theoretically, it integrates stakeholder theory, the resource-based view and brand equity theory to explain how responsible business practices create brand value through consumer interpretation. Practically, it offers insights for FMCG firms to design and communicate sustainability strategies that align with consumer expectations.

Ultimately, the study argues that authentic and well-communicated sustainability practices can serve not only as ethical imperatives but also as strategic assets that strengthen brand competitiveness and long-term value in emerging economies like Sri Lanka.

Literature Review

Overview

Sustainability has become an essential component of corporate strategy, shaping both organisational performance and brand perception. For the FMCG industry, where competition is intense and products are easily substitutable, ESG initiatives serve as powerful tools for differentiation and long-term brand equity (Kumar & Christodoulopoulou, 2014). This review synthesises key theoretical and empirical insights on sustainability, consumer perception and brand value, establishing the conceptual base for examining these relationships within Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector.

Sustainability in the FMCG Industry

Globally, FMCG companies have shifted from viewing sustainability as philanthropy to embedding it as a core strategic priority. Frameworks such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) have pushed firms to integrate ESG performance into business operations (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013). Leading brands like Unilever, Nestlé and Procter & Gamble have demonstrated that sustainable sourcing, eco-friendly packaging and waste reduction not only enhance efficiency but also strengthen brand trust and consumer loyalty (Nestlé Lanka, 2023; Unilever, 2022).

Consumer awareness has intensified this transition, as studies show an increasing willingness to pay for sustainable products (NielsenIQ, 2022). However, challenges such as greenwashing and high implementation costs remain, particularly in emerging markets (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). These realities highlight the need for transparency and consistent communication to convert sustainability actions into tangible brand value.

The Sri Lankan FMCG Context

Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector contributes significantly to national GDP and employs a large workforce (Sunday Times, 2024). Driven by regulatory measures, such as restrictions on single-use plastics, and rising consumer consciousness, companies are gradually integrating ESG principles into their strategies (Central Environmental Authority, 2023). Brands such as Nestlé Lanka, Dilmah, Kotmale, Elephant House and Keells have adopted initiatives in renewable energy, ethical sourcing and community development (Dilmah, 2023; Keells, 2023; Nestlé Lanka, 2023).

Despite these advances, limited empirical research has explored how such initiatives influence consumer perception and brand value. Economic constraints, low rural awareness and fragmented reporting remain barriers to full sustainability integration (Srivastava et al., 2024). Thus, understanding how consumers interpret these initiatives is crucial to evaluating their effectiveness.

Consumer Perception and Brand Value

Consumer perception represents how individuals interpret a brand’s actions, ethics and communications (Kotler & Keller, 2022). In the sustainability context, perception encompasses beliefs about environmental care, social responsibility and governance transparency (Peloza et al., 2012). Positive perceptions enhance trust and emotional attachment, which in turn strengthen brand loyalty and advocacy (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993).

Empirical studies confirm that authentic sustainability efforts improve brand equity through trust and satisfaction (Noh & Johnson, 2019; Saeidi et al., 2015). However, in emerging markets, perception depends heavily on communication clarity and cultural values (Jayasinghe & Fernando, 2021). In Sri Lanka, community-oriented actions resonate more strongly than abstract environmental claims, underscoring the importance of localised sustainability narratives.

Linking Sustainability and Brand Value

Evidence across industries suggests a strong positive link between sustainability practices and brand value. Firms engaging in credible ESG activities often report higher consumer loyalty, advocacy and long-term competitiveness (Ishaq & Di Maria, 2020; Jagani et al., 2024). Nonetheless, these benefits materialise only when consumers perceive initiatives as genuine and consistent. Misrepresentation or inadequate communication can damage credibility and diminish brand equity (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

In Sri Lanka, while brands such as Dilmah and Keells are widely recognised for responsible practices, systematic research quantifying how these efforts translate into consumer-based brand value remains limited. Addressing this empirical gap provides meaningful insight into the link between sustainability and branding in developing markets.

Theoretical Foundation

Three complementary theories guide this study. Stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984) explains that firms create long-term value by balancing diverse stakeholder interests through responsible ESG practices. The resource-based view (Barney, 1991) posits that sustainability initiatives, when valuable and inimitable, function as strategic resources generating competitive advantage. Brand equity theory (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993) clarifies that consumer perceptions mediate how sustainability efforts influence brand value; authentic practices enhance awareness, trust and loyalty.

Together, these perspectives establish a framework where sustainability practices drive brand value indirectly through consumer perception, a relationship this study empirically tests within Sri Lanka’s FMCG industry.

Summary

Existing literature affirms that sustainability contributes to brand differentiation and long-term value, yet its effectiveness hinges on consumer perception and communication authenticity. While global evidence is extensive, Sri Lanka lacks empirical insights into how consumers interpret FMCG firms’ ESG practices. Grounded in stakeholder theory, resource-based view and brand equity theory, this study seeks to address this gap by exploring how sustainability practices influence brand value through the mediating role of consumer perception.

Research Methodology

Research Design and Philosophical Orientation

This study adopts a quantitative, cross-sectional and explanatory research design to examine how sustainability practices influence brand value in Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector, with consumer perception as a mediating variable. Grounded in positivist philosophy, the research assumes that social phenomena can be objectively observed, measured and analysed using empirical data (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2019).

The positivist stance enables the researcher to remain neutral, applying standardised procedures and statistical tools to test hypothesised relationships among variables. This is particularly suitable for the present study, which seeks to evaluate causal relationships between ESG practices and brand value, while empirically verifying the mediating effect of consumer perception.

Positivism also aligns with the deductive approach employed here, in which hypotheses derived from existing theories, namely stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), the resource-based view (Barney, 1991) and brand equity theory (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993), are tested using quantitative data. The deductive approach ensures logical progression from theory to hypothesis testing, enhancing objectivity and replicability (Bryman & Bell, 2015; Sekaran & Bougie, 2016).

Research Strategy

A survey research strategy was selected as the most appropriate means of collecting standardised quantitative data from a large number of respondents. Surveys are widely used in consumer research because they facilitate generalisable insights into attitudes and perceptions (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The study employed a structured online questionnaire, distributed via email and social media platforms, to ensure broad geographic and demographic coverage within Sri Lanka.

This approach offers several methodological advantages such as standardisation, efficiency, cost-effectiveness due to online administration and objectivity.

The questionnaire was designed to measure the five core constructs of the conceptual framework: ESG practices, consumer perception and brand value, while including demographic questions to facilitate subgroup analysis. This strategy is consistent with prior sustainability and brand equity studies (McEachern et al., 2020; Saeidi et al., 2015).

Type of Investigation, Time Horizon and Unit of Analysis

The research is causal-explanatory in nature, focusing on determining how sustainability practices shape brand value and how consumer perception mediates these relationships. A cross-sectional time horizon was adopted, capturing data at a single point to reflect current consumer perceptions of sustainability within Sri Lanka’s FMCG industry (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Hair et al., 2017).

The unit of analysis is the individual consumer, as brand value and sustainability perception are consumer-based constructs. Each respondent’s evaluation of FMCG brands forms a distinct data point for analysis. This choice aligns with brand equity theory and stakeholder theory, which emphasise that consumer judgements translate organisational actions into brand outcomes.

Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

The study examines five main constructs derived from prior theory and empirical evidence.

Grounded in theory, the following hypotheses were proposed:

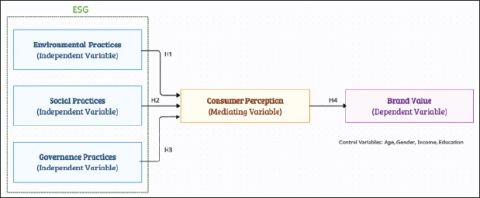

The conceptual framework as given in Figure 1 positions ESG practices as independent variables, consumer perception as the mediator and brand value as the dependent variable.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework.

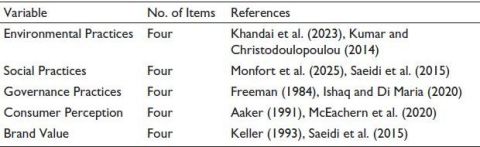

Measurement of Variables

All constructs were measured using multi-item scales adapted from prior validated instruments (see Table 1). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). This approach enables quantification of attitudes and ensures consistency across constructs (Joshi et al., 2015).

These measures were pre-tested for clarity and contextual suitability in the Sri Lankan FMCG environment to ensure both content and construct validity.

Population, Sampling and Sample Size

The target population comprised Sri Lankan consumers familiar with leading FMCG brands such as Nestlé, Elephant House, Kotmale, Dilmah and Keells. These companies were chosen due to their market dominance and visible sustainability engagement.

A non-probability purposive sampling method was applied, as it targets individuals with sufficient awareness of brand sustainability efforts, an essential criterion for valid perception measurement (Etikan et al., 2016; McEachern et al., 2020).

The sample size was determined using Cochran’s (1977) formula and Krejcie and Morgan’s (1970) guidelines, yielding a minimum of 384 participants for a 95% confidence level and ± 5% margin of error. To ensure model robustness, particularly for PLS-SEM, a slightly higher number of respondents (over 400) was targeted, satisfying Hair et al.’s (2017) ‘10-times rule’.

This sample size ensures statistical power for mediation analysis while providing diversity across demographic categories such as age, gender, education level and income, enhancing the representativeness of results.

Data Collection Procedure

Data were gathered via an online structured questionnaire, distributed through digital platforms such as email, social media and professional networks. Respondents were screened to ensure familiarity with the FMCG brands under study.

Table 1. Measurement of Variables.

The questionnaire comprised three parts:

The instrument underwent pilot testing with 30 respondents, leading to refinements for clarity and reliability.

Data Analysis Techniques

The data analysis process involved both descriptive and inferential statistical methods. Preliminary data screening and descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS, while hypothesis testing and mediation analysis were performed using SmartPLS 4, following Hair et al. (2022).

The analytical process comprised five stages:

.png) 0.70), convergent validity (average variance extracted [AVE]

0.70), convergent validity (average variance extracted [AVE] .png) 0.50) and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait [HTMT] ratio <0.85).

0.50) and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait [HTMT] ratio <0.85)..png) 0.08 and normed fit index (NFI)

0.08 and normed fit index (NFI) .png) 0.70 were applied to evaluate model adequacy.

0.70 were applied to evaluate model adequacy.This analytical approach enables comprehensive evaluation of both measurement quality and hypothesised causal relationships.

Validity and Reliability Assurance

Ensuring measurement validity and reliability was a central concern throughout the research process.

These procedures ensured that all measures accurately captured the underlying theoretical constructs, supporting credible and replicable findings.

Ethical Considerations

The study upheld strict ethical standards. Participation was voluntary, and respondents provided informed consent before beginning the survey. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured, and no personally identifiable data were collected. The research design complied with academic integrity and ethical research principles for human participants.

Summary

This study employs a positivist, deductive and quantitative approach using a cross-sectional online survey to test the relationship between sustainability practices and brand value among Sri Lankan FMCG consumers. Through a carefully structured methodology, robust sampling and rigorous statistical testing, the research ensures validity, reliability and replicability. The next section presents the results of data analysis and hypothesis testing.

Findings and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter presents the statistical findings of the study and explains how they support the research objectives. The analysis follows two main stages: (a) assessment of the measurement model to confirm reliability and validity, and (b) evaluation of the structural model to test the hypotheses developed in the conceptual framework. The results are interpreted in line with the context of Sri Lanka’s FMCG market and the existing literature provided in the thesis.

Sample Inclusion and Brand Interaction

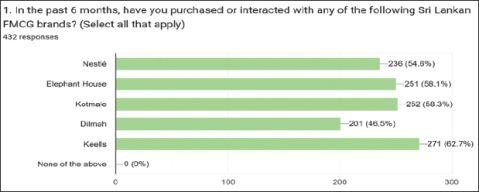

To ensure the study reflected genuine consumer perspectives, respondents were screened for recent engagement (past 6 months) with five key Sri Lankan FMCG brands: Nestlé, Elephant House, Kotmale, Dilmah and Keells (Figure 2). Of the 432 initial participants, 418 met this criterion and were included in the final analysis.

All respondents reported interaction with at least one of the five FMCG brands, confirming full sample relevance. Keells showed the highest engagement (62.7%), followed by Kotmale (58.3%) and Elephant House (58.1%), indicating strong consumer connections. Dilmah recorded the lowest rate (46.5%), likely due to its more specific product focus. This screening outcome confirms that subsequent analyses of consumer perception and brand value are based solely on active, brand-engaged Sri Lankan consumers.

Figure 2. Brand Interaction Analysis (Multiple Responses).

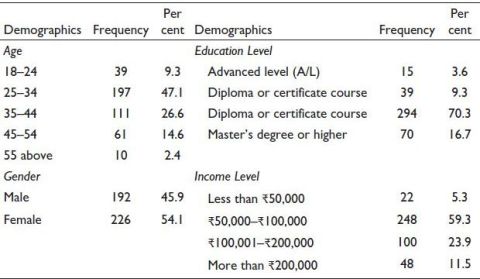

Descriptives of Demographics Data

As shown in Table 2, the sample mainly consists of young and middle-aged adults, with 47.1% aged 25–34 and 26.6% aged 35–44, together representing 73.7% of participants. These age groups are recognised for their strong awareness of corporate social responsibility and sustainability. The gender distribution is nearly balanced, with 54.1% female and 45.9% male, minimising bias in the analysis. Most respondents are highly educated, as more than 87% hold a university degree, indicating a strong capability to assess complex topics such as governance and environmental transparency. The majority earn between .png) 50,000 and

50,000 and .png) 200,000, reflecting the core middle-income FMCG consumer segment that regularly purchases branded products and values ethical and sustainable business practices.

200,000, reflecting the core middle-income FMCG consumer segment that regularly purchases branded products and values ethical and sustainable business practices.

Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model was examined to ensure the constructs used in the questionnaire were reliable and valid. Three main indicators were evaluated: internal consistency reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity.

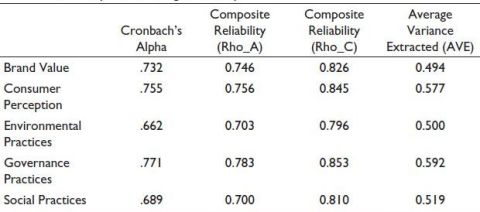

Reliability and Convergent Validity. Cronbach’s alpha, CR and AVE were used to check internal consistency and convergent validity. Table 3 summarises the results.

Cronbach’s alpha results showed strong internal consistency for governance practices (0.771), consumer perception (0.755) and brand value (0.732), while environmental practices (0.662) and social practices (0.689) were slightly below the 0.70 threshold but still acceptable for SEM analysis. The more robust Rho_A measure confirmed reliability for all constructs, each meeting or exceeding 0.70, including environmental (0.703) and social practices (0.700), supporting their inclusion in the model. CR (Rho_C) further validated these findings, with all constructs scoring between 0.796 and 0.853, surpassing the recommended 0.70 benchmark and indicating strong internal consistency.

Table 2. The Frequency and Percentage Distribution for the Key Demographic Variables.

Table 3. Reliability and Convergent Validity.

Convergent validity, assessed using AVE, was satisfactory for consumer perception (0.577), governance practices (0.592), social practices (0.519) and environmental practices (0.500). Brand value recorded a slightly lower AVE (0.494) but was retained due to its high CR (0.826). Overall, the results confirm that all constructs exhibit strong reliability and adequate convergent validity, validating their suitability for the structural model analysis.

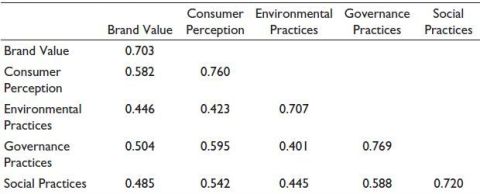

Discriminant Validity. Discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (see Table 4). The square root of each construct’s AVE should be greater than the correlation between that construct and others.

Table 4. Fornell–Larcker Criterion Results.

The Fornell–Larcker analysis confirms that all constructs meet the criterion, demonstrating clear discriminant validity. For each construct, the square root of the AVE exceeds its correlations with other constructs, indicating that each captures more variance within its own indicators than with others. Specifically, brand value (0.703) is distinct from consumer perception (0.582), environmental practices (0.446) and governance practices (0.504); consumer perception (0.760) is higher than its correlations with brand value (0.582), environmental practices (0.423) and governance practices (0.595); environmental practices (0.707) and governance practices (0.769) also exceed their respective inter-construct correlations. These results confirm that all constructs are empirically distinct, supporting strong discriminant validity of the measurement model.

Structural Model Assessment

After confirming reliability and validity, the structural model was used to evaluate hypothesis relationships. Bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples produced p values.

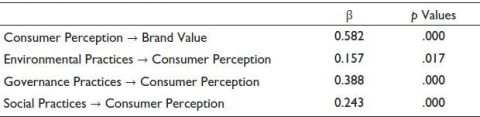

Hypothesis Testing—Direct Effects. Path coefficient results for each direct relationship are given in Table 5.

All hypothesised direct paths in the structural model are supported. The strongest effect is consumer perception on brand value (H4, β = 0.582, p < .001), highlighting that trust and ethical evaluation are key drivers of consumer-perceived brand value, emphasising the strategic importance of reputation for FMCG firms. Among the ESG dimensions, governance practices (H3, β = 0.388, p < .001) exert the largest influence on consumer perception, followed by social practices (H2, β = 0.243, p < .001), confirming that ethical governance and social contributions effectively enhance consumer trust and brand image. Environmental practices (H1, β = 0.157, p = .017) also positively affect consumer perception, though their impact is comparatively weaker, reflecting consumer scepticism towards unverified environmental claims. Overall, the results validate that sustainability initiatives enhance consumer perception, which in turn drives brand value, with the influence hierarchy being governance, social and then environmental practices.

Table 5. Path Coefficient Results.

Table 6. Mediation Results.

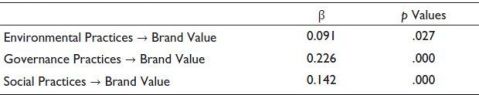

Mediation Effect. The mediation test examined whether perception acts as a mechanism through which sustainability influences brand value.

According to the findings in Table 6, the analysis confirms that consumer perception significantly mediates the effects of all three ESG dimensions on brand value, supporting H5. Governance practices show the strongest indirect effect (H5c, βIndirect = 0.226, p < .001), indicating that their influence on brand value operates largely through enhanced consumer perception. Social practices also have a substantial indirect effect (H5b, βIndirect = 0.142, p < .001), demonstrating that ethical labour and community engagement translate into brand value via consumer perceptions. Environmental practices exhibit a smaller but significant indirect effect (H5a, βIndirect = 0.091, p = .027), confirming that even modest environmental efforts positively impact brand value through consumer perception. Since both direct and indirect paths are significant, the results indicate partial, or complementary, mediation, showing that consumer perception is a key but not exclusive channel linking ESG practices to brand value.

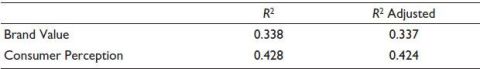

R2. The three independent variables, ESG practices, collectively explain 42.8% of the variance in consumer perception, indicating a moderate but meaningful influence on how Sri Lankan consumers assess a brand’s ethical image and trustworthiness. Consumer perception, in turn, accounts for 33.8% of the variance in brand value, also classified as moderate, confirming that the creation of this intangible asset effectively predicts market performance. The adjusted R2 values further demonstrate that the model’s explanatory power is stable and robust, supporting its strong predictive capability (see Table 7).

Discussion

The analysis reveals that ESG practices each influence consumer perception and, in turn, brand value, though the strength of these effects differs. Environmental practices positively affect consumer perception (β = 0.157, p = .017), indicating that initiatives like waste reduction, energy efficiency and sustainable packaging are appreciated but are not the primary drivers of consumer attitudes. In Sri Lanka, green consumerism is still emerging, and the impact of environmental actions is stronger when brands provide transparent, verifiable outcomes such as carbon footprint reductions or third-party certifications.

Table 7. R2 Results.

Social practices have a more pronounced effect on consumer perception (β = 0.243, p < .001), reflecting that fair labour policies, community support and health or welfare initiatives resonate with consumers. In a collectivist society like Sri Lanka, contributions to social welfare strengthen emotional engagement and brand reputation, highlighting the importance of visible social responsibility for relational and emotional capital.

Governance practices exhibit the strongest influence on consumer perception (β = 0.388, p < .001), demonstrating that ethical leadership, transparency and accountability are highly valued. Governance initiatives, including anti-corruption measures, transparent sourcing and public disclosures, serve as critical cues of reliability, building trust and enhancing long-term brand equity.

Consumer perception strongly predicts brand value (β = 0.582, p < .001), confirming that trust, satisfaction and emotional connection are central to consumer-based brand equity. In the Sri Lankan FMCG sector, where functional differences between products are limited, perceptual and emotional factors play a decisive role in shaping brand loyalty and profitability.

Mediation analysis indicates that consumer perception partially mediates the relationship between ESG practices and brand value. Governance practices show the largest indirect effect (β = 0.226, p < .001), followed by social practices (β = 0.142, p < .001) and environmental practices (β = 0.091, p = .027). This suggests that while consumer perception is a key channel through which sustainability actions influence brand value, ESG practices also exert direct effects, meaning both tangible efforts and perceived ethical conduct jointly enhance brand strength.

Overall, the findings support stakeholder and signalling theories, illustrating that consumers interpret sustainability initiatives as credible indicators of corporate integrity. For Sri Lankan FMCG firms, strategic investment in transparent governance, socially responsible programmes and verifiable environmental initiatives, combined with clear communication of these efforts, maximises consumer perception and strengthens brand value.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Researchers

Limitations

The study’s findings are subject to several limitations. Methodologically, the reliance on a cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer long-term causal relationships. While this approach is suitable for identifying relationships among variables, it does not allow for the examination of changes in consumer perceptions or brand value over time. Consequently, the ability to infer long-term causal effects of sustainability practices remains limited.

The study relied on self-administered questionnaires, which may be subject to respondent bias. Participants could have provided socially desirable responses or overestimated their awareness of sustainability practices. Although anonymity was assured to minimise such bias, the potential influence of self-report limitations cannot be entirely ruled out.

Contextually, the exclusive consumer-centred focus omits the valuable perspectives of other key stakeholders, such as employees and investors. Furthermore, the geographical and sectoral scope, which is confined to the FMCG industry in Sri Lanka, limits the generalisability of the results to other industries and cultural markets.

Recommendations for Future Research

Building on the above limitations, several directions are suggested for future inquiry.

Longitudinal research: Future studies could adopt longitudinal or panel designs to track changes in consumer perceptions and brand value over time. Such designs would provide deeper insight into the enduring effects of sustainability initiatives on brand performance.

Cross-sectoral comparisons: Extending the current model to other sectors, such as apparel, banking or tourism, would allow for comparative analyses and the identification of industry-specific sustainability dynamics. This could strengthen the external validity of the framework.

Incorporation of moderating variables: Further research could explore additional variables that may influence the strength of the ESG–perception–value relationship. Factors such as brand trust, price sensitivity and consumer knowledge could serve as potential moderators, enriching the explanatory power of the model.

Adoption of mixed-method approaches: Combining quantitative surveys with qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups or content analysis, would provide deeper insights into the motivations and cognitive processes shaping consumer evaluations of sustainable brands.

In summary, while this study offers valuable evidence on the role of sustainability practices in shaping brand value, future research should broaden the methodological and contextual scope to enhance theoretical depth and practical relevance.

Conclusion

This study provides strong empirical evidence that sustainability practices, including ESG dimensions, significantly enhance brand value in Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector. Governance practices were found to have the strongest influence on consumer perception, followed by social initiatives and environmental efforts. Consumer perception was confirmed as a key mediating mechanism, converting sustainability actions into measurable brand value, with partial mediation observed across all ESG dimensions.

The findings support stakeholder and signalling theories by showing that ethical, transparent and socially responsible practices act as credible signals that foster consumer trust, emotional attachment and brand loyalty. Consumer perception emerges as a strategic asset rather than a passive outcome. Firms that communicate and demonstrate authentic ESG practices effectively can strengthen brand equity and achieve a competitive advantage.

From a societal perspective, responsible corporate behaviour benefits both firms and communities by promoting governance integrity, social welfare and environmental stewardship. While environmental initiatives have a comparatively smaller effect, all three ESG dimensions contribute meaningfully to brand value when perceived as genuine and credible.

Overall, this research advances theoretical understanding of sustainability and brand relationships in an emerging market context and provides practical guidance for managers seeking to leverage ESG practices strategically. The study underscores that long-term brand success in the FMCG sector depends not only on operational sustainability initiatives but also on how these actions are perceived and trusted by consumers.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Rhythmani Perera  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-7509-4423

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-7509-4423

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. Free Press.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Brand Finance Plc. (2023). Brand Finance Sri Lanka 100 2023: The annual report on the most valuable and strongest Sri Lankan brands. Brandirectory. https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-sri-lanka-100-2023-full-report.pdf

Bryman, A., & Bell E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Central Environmental Authority. (2023). Ban on single-use plastic products effective October 1, 2023 [Press release]. https://www.adaderana.lk/news/92871/sri-lanka-to-ban-single-use-plastic-products-from-oct-01

Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2014). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students (4th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87.

Dilmah. (2023). Kindness. Dilmah Tea. https://www.dilmahtea.com/kindness/

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

Hahn, T., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of the literature and its implications. Journal of Business Economics, 83(5), 533–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-013-0605-3

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Ishaq, M. I., & Di Maria, E. (2020). Sustainability countenance in brand equity: A critical review and future research directions. Journal of Brand Management, 27, 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-019-00167-5

Jagani, S., Saboorideilami, V., & Tarannum, S. (2024). Shaping brand attitudes through sustainability practices: A TSR approach. Journal of Services Marketing, 38(3), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-08-2023-0345

Jayasinghe, S., & Fernando, R. (2021). Community-oriented sustainability initiatives and consumer perceptions in Sri Lanka’s FMCG sector: A qualitative study. Journal of South Asian Sustainable Development, 8(2), 123–137.

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJAST/2015/14975

Keells. (2023). John Keells Group’s crisis response initiative records promising impact among multiple communities. https://keells.lk/posts/john-keells-groups-crisis-response-initiative-records-promising-impact-among-multiple-communities

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252054

Khandai, S., Mathew, J., Yadav, R., Kataria, S., & Kohli, H. (2023). Ensuring brand loyalty for firms practising sustainable marketing: A roadmap. Society and Business Review, 18(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-10-2021-0189

Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2022). Marketing management (16th ed.). Pearson Education.

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

Kumar, V., & Christodoulopoulou, A. (2014). Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(1), 6–15.

McEachern, M. G., Middleton, D., & Cassidy, T. (2020). Encouraging sustainable behaviour change via a social practice approach: A focus on apparel consumption practices. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43(2), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09431-0

Monfort, A., López-Vázquez, B., & Sebastián-Morillas, A. (2025). Building trust in sustainable brands: Revisiting perceived value, satisfaction, customer service, and brand image. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 100105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stae.2025.100105

Nestlé Lanka. (2023). Creating shared value and sustainability report 2023. Nestlé SA. https://www.nestle.com/sites/default/files/2024-02/creating-shared-value-sustainability-report-2023-en.pdf

NielsenIQ. (2022). The challenge of sustainability: How consumers fight for their values in everyday life. https://nielseniq.com/global/en/news-center/2022/the-challenge-of-sustainability-how-consumers-fight-for-their-values-in-everyday-life/

Noh, M., & Johnson, K. K. (2019). Effect of apparel brand’s sustainability efforts on consumer’s brand loyalty. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 10(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2018.1533565

Peloza, J., White, K., & Shang, J. (2013). Good and guilt-free: The role of self-accountability in influencing preferences for products with ethical attributes. Journal of Marketing, 77(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0187

Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.024

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson Education.

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). Wiley.

Srivastava, A., Yadav, S. S., & Pal, D. (2024). Exploring the prevalence of undernutrition and consumer’s knowledge, preferences, and willingness to pay for biofortified food. In R. Kumar, S. S. Yadav, & A. Srivastava (Eds), Food security and undernutrition: Issues, challenges, and policy pathways (pp. 109–123). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4413-2_7

Sunday Times. (2024). Article about the retail industry’s contribution to GDP and employment. https://www.sundaytimes.co.za/

Unilever. (2022). Unilever sustainable living plan—Annual report. https://www.unilever.com/files/92ui5egz/production/0daddecec3fdde4d47d907689fe19e040aab9c58.pdf

Appendix

Survey Questionnaire

Instructions to Respondents:

For Section C–E, please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements by selecting the most appropriate response on a five-point Likert scale:

1 = Strongly Disagree | 2 = Disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Agree | 5 = Strongly Agree

Section A: Screening Questions

1. Have you purchased or interacted with any of the following Sri Lankan FMCG brands in the past 6 months (Nestle, Elephant House, Kotmale, Dilmah, Keells)? (Yes/No)

2. Are you aware of any sustainability or corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (e.g., eco-friendly packaging, community programmes) conducted by any of these FMCG brands in Sri Lanka? (Yes/No)

Section B: Demographic Information

3. What is your age?

[18–24] [25–34] [35–44] [45–54] [55+]

4. What is your gender?

[Male] [Female] [Prefer not to say]

5. What is your highest educational qualification?

[Up to A/L] [Diploma] [Bachelor’s] [Master’s or higher]

6. What is your monthly income range?

[Less than .png) 50,000] [

50,000] [.png) 50,000–

50,000–.png) 100,000] [

100,000] [.png) 100,001–

100,001–.png) 200,000] [More than

200,000] [More than .png) 200,000]

200,000]

Section C: Your Views on Sustainability and Brands

C1: Environmental Sustainability Practices

7. This brand actively reduces environmental pollution in its operations.

8. This brand uses recyclable or biodegradable packaging materials.

9. This brand is committed to reducing its carbon footprint.

10. I believe this brand minimises its environmental impact.

C2: Social Sustainability Practices

11. This brand supports local communities through CSR programmes.

12. The company ensures fair labour practices and employee wellness.

13. This brand promotes health, education or well-being in society.

14. The brand contributes positively to Sri Lankan society.

C3: Governance Sustainability Practices

15. I trust the brand to be transparent about its sustainability actions.

16. The company communicates openly and ethically with consumers.

17. This brand adheres to ethical business practices.

18. I believe this brand’s company is accountable for its operations.

C4: Consumer Perception

19. I trust this brand because of its sustainability practices.

20. I have a positive image of this brand.

21. I am aware of the brand’s commitment to sustainability.

22. I believe this brand is socially responsible.

C5: Brand Value

23. I would recommend this brand to others.

24. I am willing to pay a higher price for this brand.

25. I feel loyal to this brand.

26. I believe this brand offers high value.

27. This brand’s reputation influences my purchasing decisions.